The world’s first exhibition about the full-scale russian–Ukrainian war — ‘Ukraine — Crucifixion’ — opened in May 2022 at the National Museum of the History of Ukraine in the Second World War. It remains the largest-scale project of its kind, presenting the personal belongings of the occupiers alongside the stories of their failed attempt to seize control of the Kyiv and Chernihiv regions.

However, another exhibition is on display in a small space in central Kyiv, featuring around a thousand objects (by comparison, ‘Ukraine — Crucifixion’ presents about seven hundred). This project is the work of Maksym Kilderov, an artist from the occupied city of Nova Kakhovka.

And although these projects differ in their content, curatorial approach, number of exhibits, and interactive elements, they are equally important for preserving the truth and the memory of the great war.

Among the artifacts in the new museum are a Stinger missile used by an Azov fighter to shoot down an enemy helicopter, as well as two ballot boxes: one from the illegal referendum in the Kherson region, and another from the 2024 presidential elections in russia’s Kursk region. The exhibition also features uniforms and personal belongings of the occupiers.

DTF Magazine spoke with artist and founder of the museum of war artifacts, Maksym Kilderov, about the beginnings of his collection, the most interesting objects in the collection, and his desire to create a concentrated archive of wartime relics

About the collection: from Counter-Strike skins to Shahed drones

From an early age, Maksym collected gaming tokens and Counter-Strike skins. But even with a long-standing interest in collecting, in 2022 he could not have imagined that he would go on to create an entire museum of war artifacts called the World War Free Museum.

When Kilderov organized his first Kyiv exhibition at the Lavra Gallery in 2023, he already had a small collection of materials. In particular, he had used RPG rocket tubes, which he had been collecting for painting. One of these tubes he painted with the words Art Force, and it became his first ‘object of war’.

Later, a gallery owner from Miami invited Maksym to present several works at the prestigious Art Basel fair. The artist shipped them via Ukrposhta, listing the contents as ‘souvenirs’. Instead of a delivery notification, however, he received a summons to the police. In the end, the situation was resolved: ‘The local police officer was understanding’, Maksym recalls.

The same [RPG] tubes were later presented at a shawarma spot in Vinnytsia (as we reported earlier), and have now become part of a large museum exhibition.

However, Maksym did not abandon attempts to scale his work internationally. His acquaintance with Andrii Andriienko, an explosive ordnance disposal (EOD) specialist from the Ministry of Internal Affairs, gave the artist the opportunity to work with other types of weapons on a much larger scale; in particular, Andriienko provided expert conclusions required for exporting such objects abroad. Between 30 and 60 percent of the proceeds Maksym donated to support the military, while the rest he reinvested in his own experiments. But during work on an installation involving a missile, an explosion occurred, killing four EOD specialists, including Andrii. This tragedy made any further sales abroad impossible.

Переглянути цей допис в Instagram

Although more than 70 percent of the exhibition consists of items from Kilderov’s private collection, that is only part of the story: some artifacts are physically impossible to bring into the gallery — such as an entire Shahed drone.

The museum’s concept and its exhibits

The museum features artifacts from the Kherson, Donetsk, Luhansk, and Zaporizhzhia regions, as well as from the territory of the russian federation — specifically from the Kursk region and the Bryansk incursion.

There are various ways artifacts enter the collection. Occasionally, soldiers donate certain objects as a gesture of gratitude for support. More often, however, Maksym purchases them through specialized platforms such as Reibert, where defenders list their trophies.

‘I also take part in various auctions to support Ukraine’s defenders, — Maksym says. — Sometimes soldiers reach out directly, saying they’re about 50k short of buying a Mavic drone, and in return they offer a spent rocket launcher tube used moments earlier to shoot down an enemy target— accompanied by video proof. These are powerful objects with a story. So the ways things come together are completely different every time’.

The main difference from classical museums lies in the highly concentrated display of artifacts, as well as in the opportunity to interact with some of the objects.

‘In classical museums, everything is displayed separately, behind glass or cordoned off. Here, everything is concentrated. This single hall would probably be enough for six or seven traditional museum halls’.

‘I want the space to be overloaded enough to surround you from all sides. In Vinnytsia, there were cases when people who had no direct connection to the war felt physically unwell at my exhibition. No matter how it may sound, I want people to feel what war truly is’.

Despite its documentary nature, some items have been deliberately transformed into art objects — from the painted launch tubes in the Lend-Lease series to a sign from the Novoivanivka village council brought from the Kursk region, which the artist symbolically renamed ‘Novokakhovska’.

Переглянути цей допис в Instagram

One of the key sections is a collection of launch tubes of russian, Ukrainian, and Western manufacture.

‘I tried to make everything on the shelves come together into a single mass. One shelf holds dummy grenades, another features objects mostly from occupied territories. Some items exist purely to create a visual mass. It’s the same in my artistic practice: individual details have meaning, but the main technique lies in creating a unified whole’.

At the same time, Maksym notes that some objects do not align with others by category, yet they work harmoniously in terms of composition.

‘In this museum, I went against common sense — but not against composition’.

The first hall

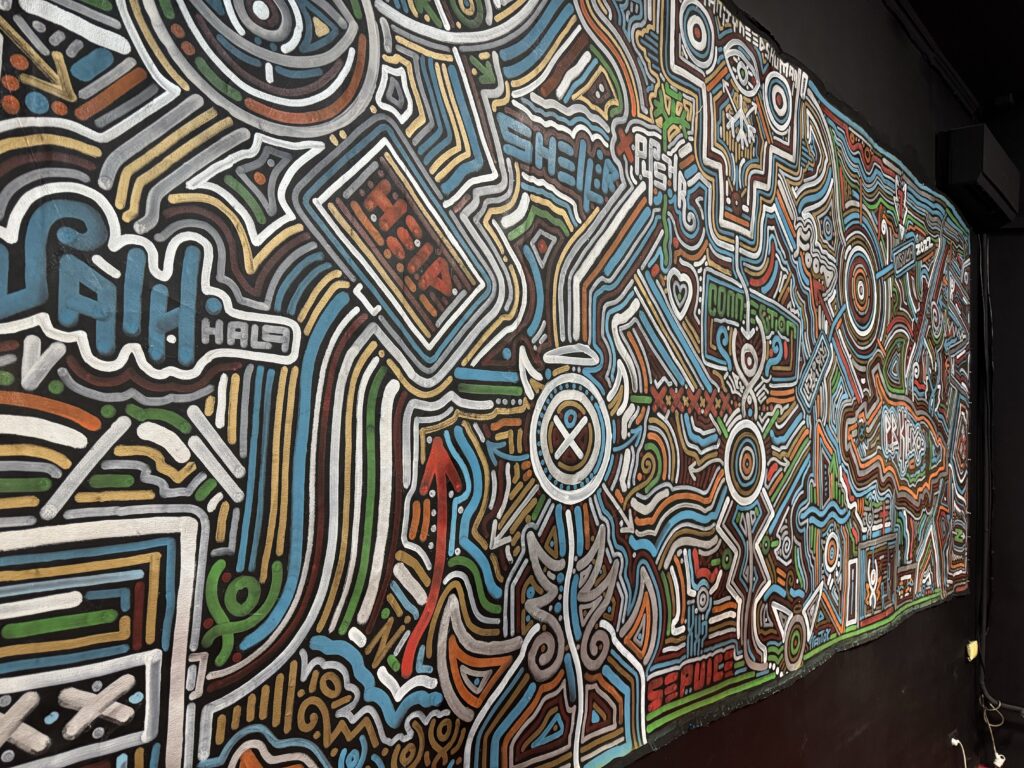

One of the first things that catches the eye is a painting by Kilderov, which the artist managed to evacuate from already occupied Nova Kakhovka in 2022.

‘This is the last blank canvas I bought before the full-scale invasion and worked on while under occupation, — Maksym recalls. — Later, I carried it through more than a dozen russian checkpoints. I hung it here because it works — both visually and conceptually. For me, it’s also an artifact of war.

In the future, Maksym plans to transform this hall into a fully fledged exhibition space ‘for artists who live in Ukraine and create objects and paintings during the war’.

On another wall, there are approximately 1,300 chevrons and patches. Among them are both official unit insignia and custom patches ‘created by servicemen or people connected to the military sphere, as well as volunteers’.

The second hall

From the vast array of exhibits, Maksym highlights several particularly significant objects. Among them are two items from the Boyko Towers. The first is a flag used by fighters of Ukraine’s Main Directorate of Intelligence when they recorded a message to the president after taking control of the towers. ‘It hung there under constant shelling. When the guys took it down, the fabric bore marks from shrapnel and areas where the material had literally melted’, Maksym recalls.

Next to it is a PlayStation console that defenders played on at the same Boyko Towers. The museum plans to keep it functional, allowing visitors to play the very same games the Ukrainian fighters played.

Maksym won a Kraken unit flag signed by fighters of the special forces unit at a charity auction.

‘Later, I began to have doubts about the organizers of that auction, so I sent a photo of the flag to a friend who has been with Kraken for a long time, — Maksym says. — When he saw the signatures, he broke down in tears: among them were the names of those who stood at the unit’s origins — and many of them, unfortunately, are no longer alive’.

A Stinger MANPADS used by an Azov fighter to shoot down a russian helicopter in the Zaporizhzhia direction.

The exhibition also features a ballot box from the illegal referendum on the ‘accession’ of the Kherson region to the russian federation. Inside are dozens of authentic ballots. Maksym emphasizes their authenticity, noting that forgeries are common on the market.

There is also a large interactive table featuring a hundred objects — ‘things you can turn over in your hands and examine closely’. Among them are a traditional knife belonging to an occupier from Yakutia, documents, radios, watches, chevrons, and night-vision devices. On a nearby table are more items left by the occupiers: playing cards with pornographic imagery, a russian officer’s planner from the so-called LPR containing notes about the filtration of Ukrainians, a daily schedule, and what Maksym describes as a ‘vast amounts of information’.

Maksym notes that they are in communication with the director of the National Museum of the History of Ukraine in the Second World War regarding potential collaborative projects, but there are no details yet.

‘I also handed over two original videos from the period of occupation that I filmed myself. Currently, they are being presented at an exhibition in London, which was co-created by this museum’.

The museum of war artifacts is not yet open to the public. You can follow for updates here.