The Mykolaiv Young Photography School (MYPH) has announced the finalists and winners of the second MYPH Photography Prize. In total, the jury selected eight Ukrainian photographers: Anastasiia Leliuk, Yehor Hushchyn, Ania Tsaruk, Dara Petrova, Yelena Kalinichenko, Mariia Hyrladzhyu, Mark Chehodaiev, and Oleksii Chariei. Their works will be on view at Dymchuk Gallery (21 Yaroslavska Street) until November 16.

DTF Magazine takes a closer look at the projects by the winners and finalists of the MYPH Prize’25, featuring a selection of their key works

Winners

1st place — Oleksii Chariei, ‘My Own Virgil’

‘On the morning of February 24, 2022, we all woke up in a new reality — one in which missiles were falling on Kyiv, and russian tube artillery was already within firing range of the city’s outskirts. I wrapped up all my urgent business and headed to the recruitment centers to join the military.

At first, I photographed everything around me, but at some point it became clear that this was not a project about civilians who became soldiers. It is a story about the soul’s journey toward healing — through an honest confrontation with the most terrifying and most vile manifestations of human nature, set against the backdrop of a war for survival against an old and very powerful enemy. It is a journey in which an inner Virgil leads me through the circles of hell, and I must face all these vices, honestly seek them within myself, and accept their existence.

Helplessness, irresponsibility, betrayal, the thirst for profit at any cost, hypocrisy, and lies. We all walked this path, and those who had enough inner strength became stronger and more authentic. This is my story, told through documenting the lives of my brothers-in-arms. It is a story about hope that leads us through the darkest times.

I thought that I had seen it all, drawn my conclusions, and accepted everything back in the autumn of 2022. But it turned out to be a transition into a new cycle. Since then, there have been two more such cycles. The project continues’.

2nd place — Mark Chehodaiev, ‘Hotel Europa’

‘‘Hotel Europa’ is a project that explores places which were once part of Austria’s tourist infrastructure — intended for temporary stays, leisure, or recreation. Today, these spaces are in a state of decline; they are technically and conceptually outdated. Former hotels and resort complexes have lost their original purpose and are now used as shelters for people fleeing the war in Ukraine, and in some cases for refugees and displaced persons from other parts of the world.

These places and their residents coexist in a strange state where the ‘temporary’ becomes permanent. Due to financial constraints or health reasons, many people have not integrated into the new country and lead secluded lives within the hotels, often having no contact with the cities they reside in. Lacking a safe home, people cannot choose their environment and are forced to adapt to the conditions available, reshaping their needs accordingly. At the same time, the places themselves are transformed — their image and essence are shaped by the presence of new inhabitants.

The core of the project is a series of photographs of the interiors of these locations and of everyday life — in private rooms and shared spaces. Using a film camera, I document this in-between reality and, more broadly, the less visible ‘side effects’ of war and forced displacement’.

3rd place — Yelena Kalinichenko, ‘I’m not fine’

‘‘I’m not fine’ is a project that explores the psychological impact of war on civilians. Rather than focusing on the war itself, it centers on how people cope with trauma, anxiety, and PTSD, revealing invisible emotional experiences and what happens when people allow themselves to be vulnerable.

I plan to create several stories that combine artistic and documentary photography with poetry. For now, I am sharing the first story with you — my own. It is a personal exploration of anxiety disorder and constant grief. Life became unbearable after my partner joined the army and I was left alone. This is my attempt to meet pain face to face and to honestly answer the question so often asked in Ukraine: ‘How are you?’

The photographs were taken during blackouts using a flashlight.

This project is important because today the experience of war is shaped by the constant influence of news and social media, creating intense psychological pressure even for those far from the front line. This reality permanently changes our lives and will likely affect the next generation as well’.

Finalists

Anastasiia Leliuk, ‘Impossible to Hide’

‘In this photo project, I work with themes of vulnerability and exposure, exploring how war alters the perception of physical embodiment. Here, the body is perceived as more than just a given — depending on the situation, it becomes a tool, a means of survival, or a burden, yet always remains fragile despite its potential strength’.

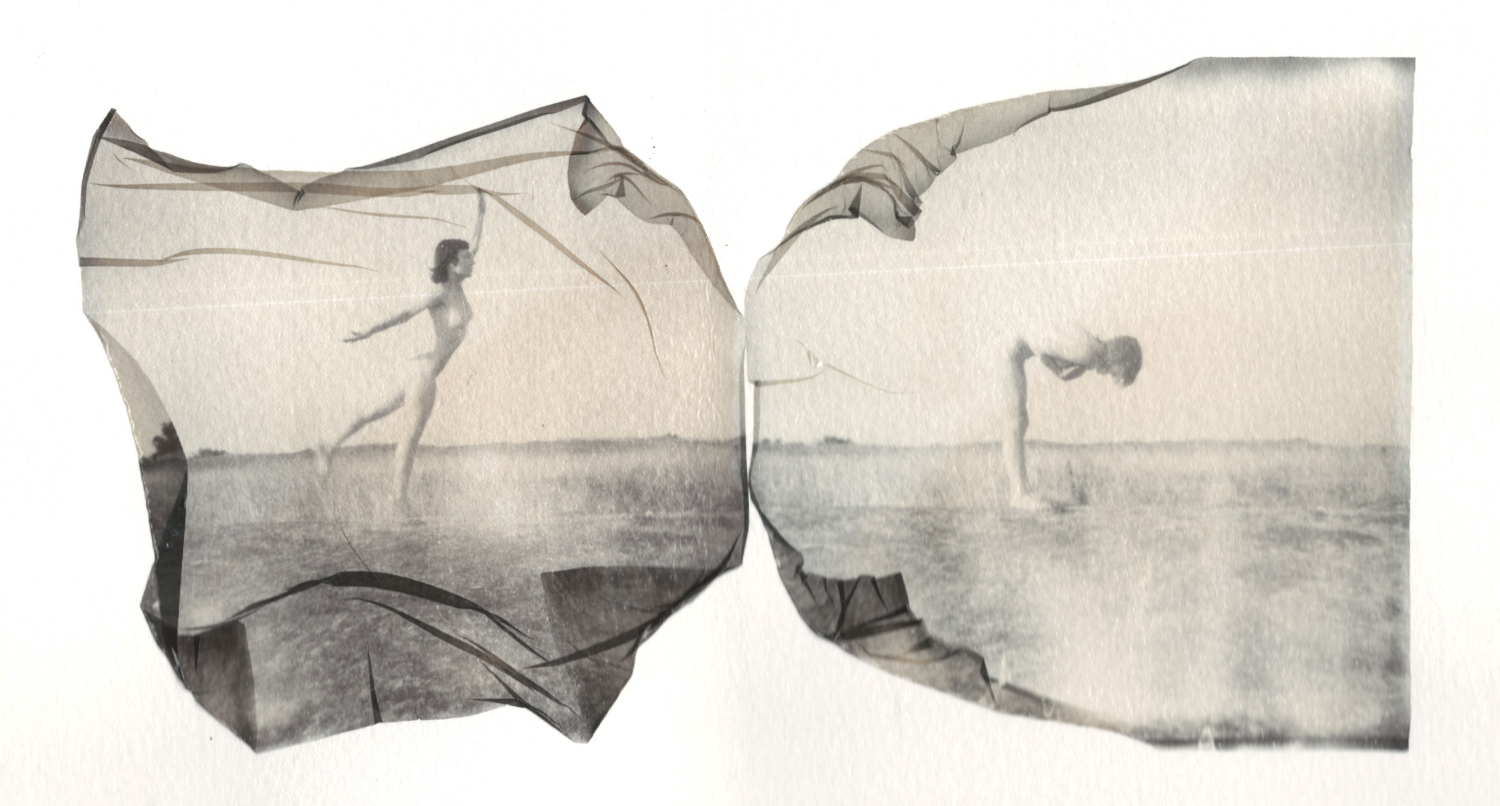

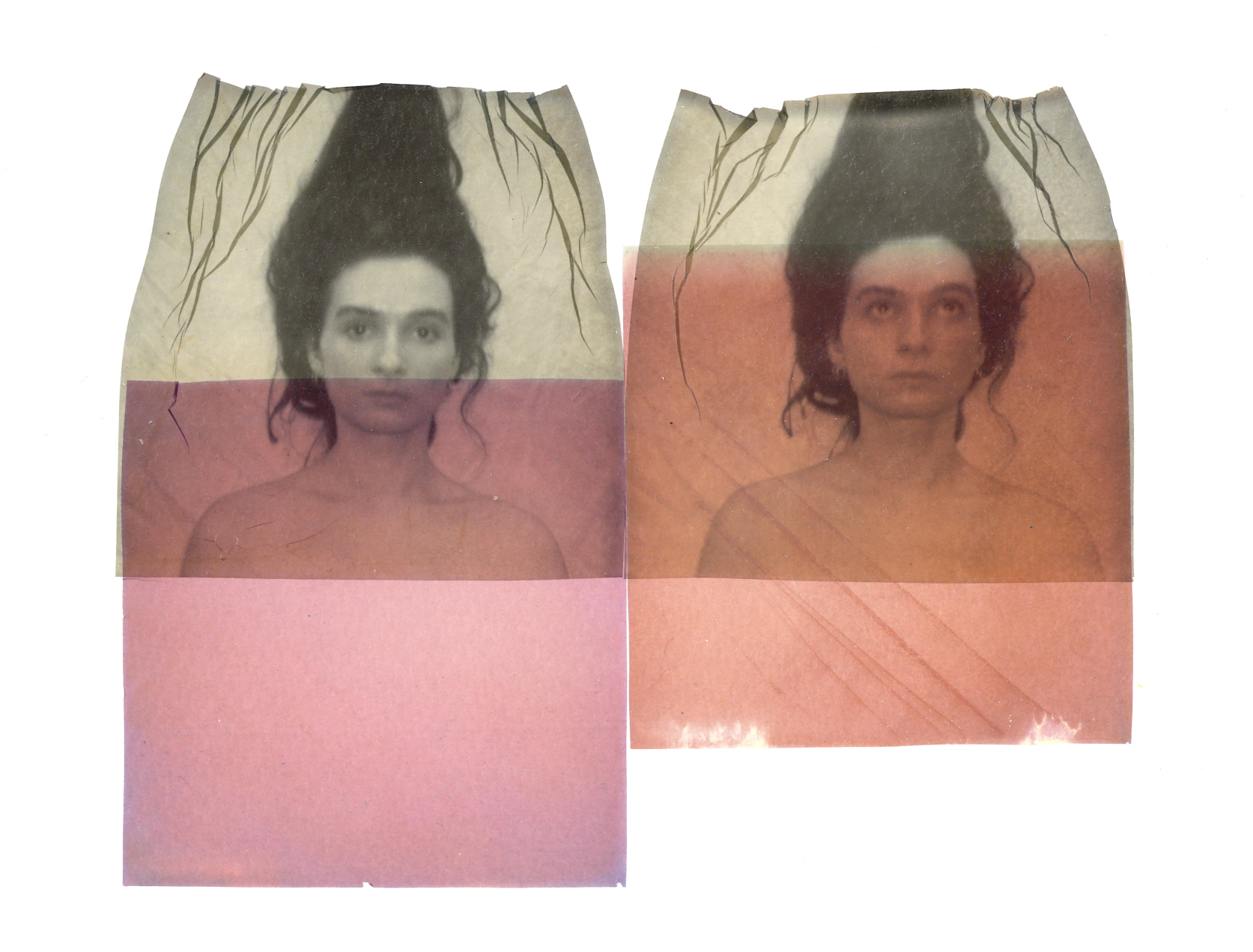

Maria Hyrladzhyu, ‘Resistant Soul’

‘The project was born in the spring of 2024 as an intimate reflection on my own state during the war. At that time, I was haunted by a sense of uncertainty: whether tomorrow would come, whether a future would remain. I chose the Polaroid emulsion lift technique because the fragile, deformed emulsion itself becomes a metaphor for the human soul in wartime. It is altered, damaged, subjected to external pressure, yet it preserves the image, continues to exist, and even finds a new form. This is an act of resistance — survival after deformation’.

Dara Petrova, ‘The Circle’

‘This is a visual study of civilian life in Ukraine, documented far from the front line. The war affects everyday life quietly, yet perceptibly.

What does war do to people? Does it kill? Yes. Does it maim, wound, or leave them shell-shocked? Yes. But that is not all.

When we look for images of war, we almost always see the front line: explosions, smoke, blood, soldiers. But war is not only shelling. It is much broader. Much quieter. It lives in tired gestures, in tense silences, in uncertain growing up, in slow conversations about the weather. In real life, people do not shoot, hang themselves, or confess their love every minute. More often, they eat, drink, pass the time, and talk nonsense. And this, too, is part of the war. We just rarely notice it.

This project is about people living in the rear. Veterans returning home and undergoing rehabilitation. Teenagers growing up amid uncertainty. Villages where everyday rituals continue.

‘The Circle’ is a record of Ukrainian life into which the war has quietly seeped. It is a reflection on a state of being. On an everyday reality where the wound does not scream. It exists’.

Ania Tsaruk, ‘I Hope Your Family Is Safe’

‘I have heard these words countless times since the beginning of russia’s full-scale invasion, and I still don’t know how to respond to them. What does safety mean in a country at war?

Born and raised in Ukraine, I moved abroad nine years ago. Since then, I have never felt such a strong desire to return as I do today — to see how my homeland has changed, to look beyond the simplified image often created by the media, which portrays Ukrainians solely as victims trapped in tragic circumstances. What does my Ukraine look like today?

I find myself at a loss for words and look for visual clues instead. A window damaged by a missile strike, trenches where my father underwent military training, a wedding suit and mourning headscarves hanging side by side at a market. I hear that our neighbor’s brother was killed at the front, and that my uncle has been mobilized. I see a black-and-white photograph of a childhood friend on the Alley of Fallen Heroes.

Death is everywhere here, and at the same time — life. A crowded city beach on a Sunday, a friend’s newborn child, my grandmother’s chicks. Ukrainians fall in love, adopt dogs, volunteer, and celebrate Christmas. Love, joy, and beauty coexist here with immense pain and tragedy. I see my people in their resilience, dignity, and inexpressible longing for freedom.

In my country, filled with trauma and torn apart by war, I feel as alive as nowhere else. I am in danger because of russian missiles. I am safe because this is my home’.

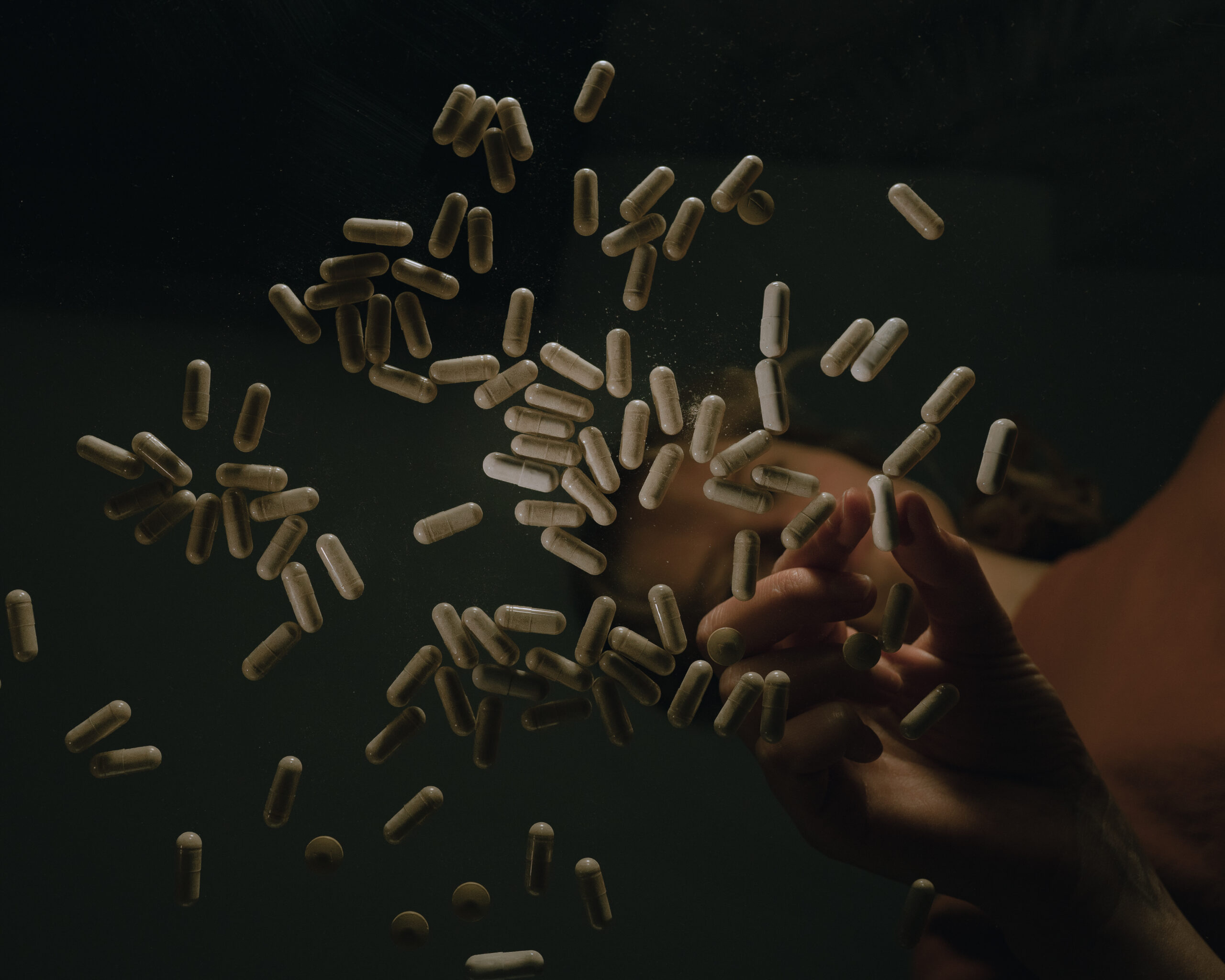

Yehor Hushchyn, ‘Too Late to Die Young’

‘Our generation grew up in a world shaped by freedom and endless possibility. We weren’t constrained by the dozens of eyes of gadgets; we were left to our own devices, and in that there was a wild, authentic beauty. Drugs and alcohol were part of our everyday reality, and many of our peers romanticized the idea of dying young, burning brightly and quickly. They remained there, in eternal youth.

Someone might call us a lost generation. But we are not your legends or heroes — we are ordinary ‘knights of the road,’ who have walked our own path, surviving personal apocalypses, a global pandemic, and the baptism by fire that is war. My youth passed quickly, forcing me to grow up too early, too abruptly. Throughout this journey, I kept moving in search of my own truth, neither wholly good nor entirely bad. And it was this path — this continuous search — that became a new meaning: a reason not to die young.

No one can take away our right to dream, to remember warm moments, and to find beauty in each new day. Because our hearts are still full of that reckless, youthful hope. This is a story of survival, of accepting one’s own path, and of the fact that life, even after all the trials, still offers new meanings’.