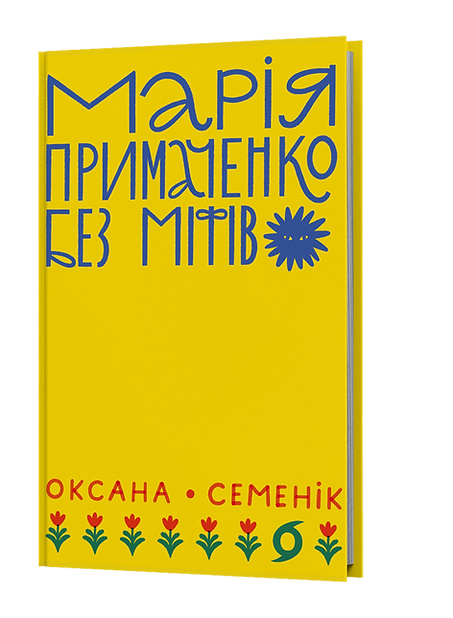

The publishing house Vikhola has released a book by art historian Oksana Semenik titled ‘Mariia Prymachenko Without Myths’. The author promised to write the book in March 2022 while living under occupation in Bucha. She dedicated it to her mother-in-law, Nataliia Viktorivna, who passed away in the summer of 2025 due to cancer.

In the foreword to ‘Mariia Prymachenko Without Myths’, Oksana Semenik writes that her work does not claim to be ‘a complete biography or a comprehensive study’ of the artist. Instead, it is an attempt to explore Prymachenko’s life, in which ‘personal tragedies intertwined with global events’, as well as an effort to debunk the most common myths and stereotypes about the painter. At the request of DTF Magazine, Oksana shares more about her book

— Why Mariia Oksentiivna?

— I can no longer say exactly how many years ago the idea of writing a book about Mariia Prymachenko first came to me, but it was a long time ago. I was struck by the absence of a publication that finally deconstructed the image of the naive rural woman who painted kind animals. I truly couldn’t understand why one of our most popular artists remained so under-researched, confined to the stereotype of a naive grandmother.

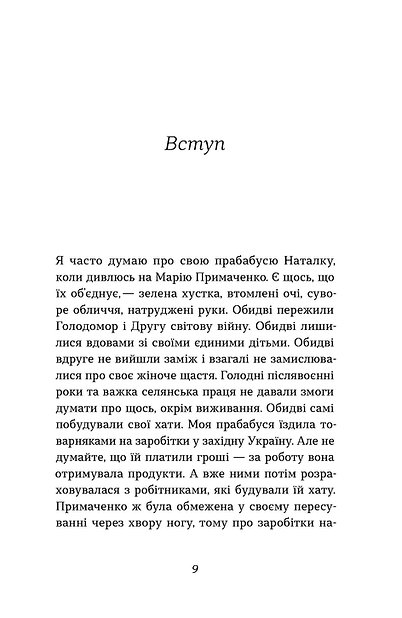

I kept postponing this research, this book, thinking that it would require time and resources, and that perhaps I wasn’t yet ready for this story. But when the full-scale invasion began, and Bucha, where I was living at the time, fell under occupation, and we were forced to live in the basement of a kindergarten, I needed something to think about, something to keep my mind occupied. That was when I promised myself that I would finally write the book about Prymachenko — because, really, there was no reason left to postpone it.

In the autumn of 2023, the Ukrainian Museum in New York opened a major solo exhibition of Mariia Prymachenko and invited me to write a research essay for the exhibition catalogue. While working on that text, I realized what was missing and what exactly I wanted to explore, which allowed me to form the structure for my future book.

And in conversations with Vikhola, we came to the conclusion that it would be great to create a research-based book about Prymachenko — a nonfiction work for readers who are not art historians or scholars — so that people could simply learn more about her and understand, as in ‘Twin Peaks’, that the owls are not what they seem. And that Mariia Oksentiivna is far greater than the images and myths that surround her figure.

Because her work has long been perceived — and is still perceived — as the aesthetic of strange, kind animals, even though not all of her creatures are kind, nor are they senseless or primitive. Personally, I am interested in Prymachenko as an artist in whose work both good and evil are present. On the one hand, her art is very bright and hopeful — she speaks a lot about the beauty around us, which must be noticed and protected.

She is full of light — this is deeply felt in her works. At the same time, her life was marked by great pain, from illness in childhood to the Chornobyl disaster, which occurred just 50 kilometers from her home. Her art also contains a great deal of critique — she created many works on the themes of the Cold War and the nuclear threat, and was one of the very few artists in the USSR to work with these themes openly.

It is fascinating to think, for example, that if she hadn’t practiced embroidery, and if one day at a market her embroidery had not been noticed by the embroiderer Tetiana Floru, who was selecting rural talents to work on the 1936 folk art exhibition, we might never have known who Prymachenko was. Or perhaps we would have learned of her eventually — but much later. And if the Ukrainian Sixtiers had not known about her, had not helped her with paints and paper, and supported her path to receiving the Shevchenko National Prize, she would have created far fewer works.

It feels like a great challenge to write a book about Mariia Prymachenko. First, I am fully aware that this is far from a complete study — absolutely not. Second, her genius, worldview, and art are things that no one will ever fully understand. One can only come a little closer to them, but we will never truly know how her imagination worked, what ideas guided her, or what she herself thought about all of this. She did not leave us an autobiography, did not keep diaries, and did not give endless interviews every day.

— How did the work on the book unfold?

— I had the opportunity to study the largest collections of Mariia Prymachenko held in Ukrainian museums and private collections: the National Museum of Decorative Arts of Ukraine, the National Museum of Folk Architecture and Life of Ukraine, the Taras Shevchenko National Museum, as well as the collections of Eduard Dymshyts and the Ponomarchuk family, and works from art museums in Khmelnytskyi, Chernihiv, and other cities. Altogether, I was able to see around fifteen hundred of Prymachenko’s works and work closely with their inscriptions. She didn’t just sign nearly every piece with a short title; she told an entire story — what she was depicting, why she chose it, and more.

I also consulted Prymachenko’s personal file at the National Union of Artists of Ukraine, as well as archival materials — in particular the archive of Hryhorii Miestechkin, an art historian and journalist who was among those who ‘rediscovered’ Prymachenko during the Soviet period. I worked with materials from the collection of the Central State CinePhotoPhono Archive named after Hordii Pshenychnyi, and with recollections of the Sixtiers found in newspapers, magazines, and various media sources.

Was it really as difficult to find materials about Prymachenko as it is, for example, to work with avant-garde artists who have left almost no traces in Ukrainian archives? No — but unfortunately, I did not have the opportunity to work with the artist’s family archive. I leave this to other researchers, who will hopefully discover and study what I was unable to find and examine.

— Weren’t you afraid that since Prymachenko is one of Ukraine’s most mentioned and high-profile artists, there would inevitably be people who would argue that you were wrong about something?

— That fear emerged even before the book was released — I heard many comments claiming that I was creating an image that never actually existed. One of the myths suggests that art historians were ‘prompting’ her or helping her paint, and that she herself wouldn’t have been capable of creating critical works on socio-political themes. In my opinion, such views deeply devalue the artist as a whole. It reflects certain stereotypes — the assumption that if a person comes from a village and does not have a higher education, they must be ignorant and incapable of understanding what is going on.

I managed to speak with the late ethnographer Lidiia Orel, who studied Polissia and at one point curated Prymachenko’s collection for the Museum of Folk Architecture and Life. This is, in fact, perhaps one of my favorite collections — works the artist created in the 1970s. Many of them focus on the theme of war and depict ‘beasts’ as a response to the repression of Ukrainian culture and of her friends.

Orel described Prymachenko as a very wise individual. Many of those who knew her also recall that the artist had an intuitive sense of people — she could tell who came to her and with what intention. She wasn’t friendly with everyone, nor did she invite or welcome everyone into her home. I understand where this stereotype comes from: in russian-language journalistic texts, it is often claimed that Prymachenko and her son had speech impediments and spoke very poorly. Instead of recognizing this as a Chornobyl-area dialect, those authors interpreted it as some kind of speech disorder.

As for criticism, it might be about something missing from the book, or there could be questions regarding my research methodology, the way I wrote the text, or the words I chose. Criticism can be directed at anything, but that is actually quite normal.

— In the introduction to the book, you write that despite Prymachenko’s ‘prominence’, we actually know very little about her. Why do you think that is?

— I’d like to point out right away that, in fact, we don’t know much about the history of Ukrainian art in general. Perhaps the question should not be why we know so little about Prymachenko, but rather why we know so little about Bilokur, Vasyl Krychevskyi and Fedir Krychevskyi, Murashko, and many others.

Prymachenko, in fact, regained prominence and became even more popular in 2022 following the destruction of the Ivankiv Historical and Local History Museum. The museum was damaged on the third day of russia’s full-scale invasion, when a fire broke out after it was hit by four missiles. Until the de-occupation of the Kyiv region, it appeared that the works stored there — including her early pieces — had been destroyed. It later emerged, however, that museum staff had managed to save part of the collection.

And it is a truly remarkable story, one that says a great deal about how local people perceive Prymachenko’s paintings — this heritage is so vital to them that they were willing to risk their lives for it. In the end, that heroism paid off: it reminded Ukrainians of Prymachenko and brought renewed attention to her work abroad. Because the idea that she was widely known internationally before the full-scale invasion is another myth. She never had major solo exhibitions until recent years, when her work was shown in Warsaw, Malmö, Vilnius, and New York.

— For many people, Prymachenko is, roughly speaking, about horses and dogs — a cute, playful aesthetic that is also very easy to turn into merch. That’s not a bad thing, because art is also about aesthetic pleasure, not only about deep meanings. At the same time, what do you think Ukrainians should know about Prymachenko first and foremost?

— She truly was a natural talent. At the same time, she studied in the workshops at the Kyiv Pechersk Lavra, where she was exposed to folk art from other regions. So the idea that she emerged from folk art traditions like painting houses is another stereotype. In the Polissia region, people didn’t actually paint their houses. Her work was shaped much more by the tradition of embroidery.

Her story is a very positive one. She was supported by her parents, who did not forbid her from pursuing art. As a single mother with a disability, she did not give up art, did not lose her sense of light, hope, or trust in people, and continued to create — she was highly productive and worked relentlessly.

We also need to understand that when she created the main body of her work, she was already over sixty. It was only then that she finally had the opportunity to draw and create fully. Realizing that she did not know how much time she had left, she threw herself into her work and was extraordinarily productive, despite the challenges posed by her disability. Prymachenko was a woman of extraordinary strength, whose imagination knew no boundaries — and that is truly inspiring.

When we talk about so-called naïve art, self-taught artists often depict their emotions, experiences, or themes such as war in a very literal way — tanks, soldiers, burned houses, and the like. Prymachenko, however, approaches these subjects through storytelling and from multiple perspectives, never depicting them literally. When she addresses the war she lived through, she speaks about memory, fallen soldiers, and their sacrifice. When she reflects on the threat of nuclear war, she imagines it as a terrifying beast that devours and destroys everything.

Her art evolves in harmony with the events of her life. For example, the works of the 1970s reflect a period when Ukraine’s Sixtiers were being repressed — people Prymachenko knew personally: Alla Horska was murdered, and Serhii Parajanov was imprisoned. Prymachenko should never be perceived as someone detached from the world or the events surrounding her. The image of Mariia Oksentiivna as a naïve artist who painted only kind animals was constructed over a long period of time, beginning in the Soviet era.

It’s hard to say whether this was, in fact, an advantage, as she wasn’t perceived as a threat. For exhibitions, curators mostly selected works associated with folklore — those same kind animals or flowers. By not highlighting the pieces she created about war, the nuclear threat, or her critiques of socialist competition, she remained a ‘safe’ artist for the authorities — one who did not need to be repressed or banned.

— Which myth about Prymachenko bothers you the most?

— The myth that Pablo Picasso supposedly called Prymachenko a genius, and that if the Spaniards had such an artist, they would have made the whole world talk about her. Similar pseudo-quotes, by the way, appear not only in connection with Prymachenko but also with Kateryna Bilokur. What bothers me most is that these claims are still mentioned even in very brief biographical notes about who Prymachenko was.

In my opinion, such quotes highlight a sense of inferiority, as if it’s vital for us that our artist be recognized by some white European man already established in art history. As though without his validation, she would no longer be considered such a great artist.

This pattern constantly reappears in discussions of Ukrainian women artists who come from rural backgrounds and lack formal academic training. For instance, I’ve seen mentions that Henri Matisse supposedly admired Hanna Sobachko-Shostak. This fact is intended to make Ukrainians realize that such art is worthy of recognition simply because someone authoritative admired it. Meanwhile, Oleksandra Ekster deeply admired Sobachko-Shostak, and they worked together in the Verbivka workshop in the Cherkasy region.

I’ve discussed this several times with journalists and even museum professionals. They don’t see anything wrong with it, even if it’s a fabrication or a complete myth. In my view, the issue isn’t just that Picasso or Matisse never actually said those things; it’s the fact that we feel compelled to bring it up at every opportunity. It’s as if this alone makes Prymachenko an artist worthy of being included in the history of world art. In other words, we’re talking about hierarchies: Picasso is positioned as someone ‘above’, while Prymachenko is implicitly cast as a lesser artist.

Of course, such unspoken hierarchies exist, because when we talk about the history of world art, we very often mean the history of Western European art and, perhaps, that of the United States — and, of course, russian art. Unfortunately, artists from the so-called ‘periphery’ aren’t always included in this global canon. And we only reinforce these hierarchies instead of, for instance, discussing how Prymachenko was creating her fantastic, experimental beasts at the same time as Picasso was working on ‘Guernica’. That would open up a truly fascinating dialogue between equal forms of art and equal artists.

Today, many museums of contemporary art include the work of so-called self-taught artists in their permanent exhibitions — often referred to as raw art, outsider art, or art brut. Thankfully, we have at least reached the point where Prymachenko is no longer described as a naive artist, although I still encounter recent references that classify her as a representative of so-called primitive art.

In other words, there is a global shift toward inclusivity, a broadening of how we view artistic processes and art history in general. For this reason, I see no problem in speaking about Prymachenko as a figure who should be understood not as a decorative or folkloric artist, but as an artist with a worldview that she articulated through her work, while constantly experimenting and searching for her own visual language.