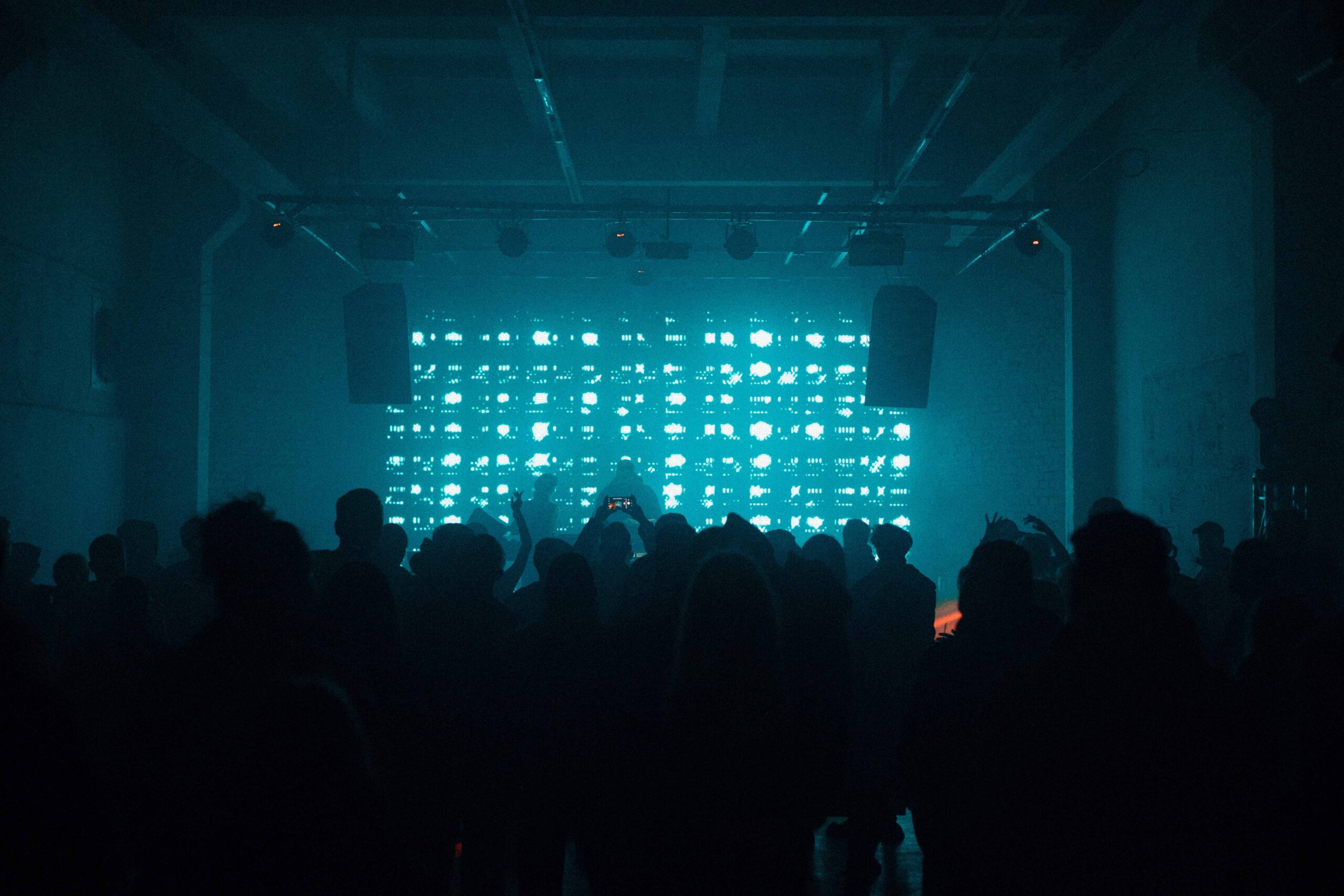

For clubs, industrial areas and buildings are a natural environment. Why? They are located farther away from residential areas and central or tourist parts of the city, they are cheaper to rent, more visually appealing, and provide more opportunities for experimentation.

Berlin is the most famous city where abandoned factories, power plants, and similar spaces were squatted and repurposed. However, Kyiv has followed the same path, although not on such a large scale and somewhat later. Among the most striking examples are the former ribbon-weaving factory on Nyzhnioyurkivska Street, where Closer first started operating, and later other clubs, concert venues, galleries, and vinyl stores; ‘Club on Kyrylivska’ — in the building of a former Kyiv brewery dating back to 1872; and, for the past three years, some of the largest electronic music events have been taking place in the pavilions of the Dovzhenko Film Studio, built in the late 1920s.

There are also plenty of examples in other Ukrainian cities: in Lviv, the TRACE club opened in one of the workshop halls of the former Lviv glass and mirror plant; Kharkiv’s group Some People is building the Center for New Culture, an important part of which is the club, in the building of a commercial machinery plant; and the ‘Detaliзація’ (Detalizatsiia) festival in Ivano-Frankivsk was held in 2019 in the abandoned buildings of the canteen and gym of the Avtolyvmash plant.

In fact, the ‘Detaliзація’ festival, which was held this year for the first time since the start of the full-scale war with the support of the EU House of Europe program, hosted a discussion panel dedicated to how former workshops and factories become places of art, music, and new communities. Its participants were Slava Lepsheiev, founder of the most famous Ukrainian rave Cxema; Anton Nazarko, co-founder of the Some People formation; and Kseniia Yanus, co-founder of the ‘Noiz shchoseredy’ (‘Noise every Wednesday’ — note by DTF Magazine) event series, who moderated the discussion.

DTF Magazine, together with House of Europe, presents the most interesting highlights from the discussion.

ON THE ADVANTAGES OF INDUSTRIAL SPACES

Kseniia: Slava, why did you choose industrial locations for Cxema? I know your event started in Otel’ (a club on the territory of the revitalized ribbon-weaving factory — note by DTF Magazine). You also held Cxema in CultMotive, a former bakery on the banks of the Dnipro River, and there was also a Cxema event in Berghain.

Slava Lepsheiev: Yes, we started in 2014, and one of the first locations was indeed the Otel’ club. At that time, the ribbon-weaving factory was a new space, and Closer was the pioneer — it had already been operating for a year when I found Otel’.

Later, when the number of people wanting to attend Cxema increased, we started looking for a larger space. Practical considerations played an important role here: a large area should be cheap, located away from the center and residential buildings, and free of walls and columns. That is, it must be a warehouse, hangar, or former factory.

There is, of course, an aesthetic aspect — the look and feel of the space. An old industrial building made of brick and concrete makes you want to do something no one has done before.

On the other hand, we held Cxema at a relatively modern Tetra Pak factory, built in the 1990s by a foreign company. All my youth, I drove past it and thought: ‘Wow, what a great building, so well built’. Over time, it was bought out, Tetra Pak moved out, and it turned out it could be rented. We held two events there.

Kseniia: Anton, as far as I know, you are repurposing a building of a former Soviet-era factory in Kharkiv…

Anton Nazarko: Yes, we’re building the Center for New Culture in a former commercial machinery plant, where refrigerated display cases for stores were produced in Soviet times.

Besides aesthetics, which Slava already mentioned, practicality plays an important role in choosing an industrial facility.

For example, after World War II, Kharkiv was developed as an industrial city, so there is not as much necessary infrastructure in the city center as in factories. What do I mean? Before the full-scale war, when we first thought about creating the Center for New Culture, we had the opportunity to rent a very cool historical building right in the city center without residential buildings nearby for a small amount of money. It could have been a wonderful cultural center. The owner was practically giving it to us, and we had already started thinking about implementation… But then we ran into a problem — a lack of electricity capacity. To conduct additional power, we were told we’d have to pay an astronomical sum — around $200,000. So practical aspects are always important ones to consider before renting.

The money issue also works in favor of industrial facilities — they are cheaper to rent. We decided we would pay rent properly and not use spaces owned by the state, the region, or the city. Because if you want to build a truly independent platform that influences what happens in the city, you have to be truly independent. So that at some point you’re not asked to get involved in the next elections.

Slava: Unlike Anton’s project, for me industrial premises are for one night only. My main goal is to find a place that people will visit for the first time. Industrial spaces are a new experience for visitors. In this sense, I’m always searching for new spaces.

Read also: ‘Everything was created from scratch’. Architect of ∄ tells the story of the club construction

ABOUT RETHINKING FOR ONE NIGHT, LONG-TERM DEVELOPMENT, AND CONTINUOUS UNCERTAINTY

Kseniia: Often industrial spaces are reimagined just for one night. Slava, how do you feel after an event? Do you want to go back to the same place again?

Slava: The feeling after the event is very draining because preparation lasts for several months. Mentally, emotionally, and physically, it’s exhausting. When it’s over, there’s a feeling of ‘We did it! It was cool’, but you still feel depleted. Then you realize you have to look for a new place for the next event.

I have thought about finding a permanent venue — smaller, not for 2,000 people or more. There are good examples: Berlin’s Berghain and Kraftwerk, where the Tresor club operates. Kraftwerk, like Berghain, is a former power plant building. In 1997, Dimitri Hegemann found an abandoned building to reopen the famous Tresor club. The Berlin Atonal festival of avant-garde music and art also happens there, along with fairs and large exhibitions. So the space serves multiple purposes. I want to find an opportunity to open something like that in the future.

Kseniia: Anton, how do you deal with constant uncertainty? You rent a space, invest in it — but at any moment it could be redeveloped, or the lease terms might change. How do you stay motivated?

Anton: That’s our headache, honestly. When we decided to create the Center for New Culture, we didn’t have resources to build from scratch. But we had no option but to do it because we saw what was happening to our city, which we love deeply. At some point, we just asked: do we do it or not? We decided we couldn’t help but do it.

We signed a lease and started looking for money for rent and deposit. Everything that happened after was a fortunate chain of events involving people who love their city and are loved by it. We’ve been involved in cultural projects for over 10 years, working in creative industries, creating places, and gaining experience.

We signed a good six-year contract. What happens after, we don’t know yet. We hope to continue our work there. We have good relations with the owners, who are patient and understand the difficult circumstances we’re working under. They recognize that there aren’t many young people and cultural initiatives left in the city, so they respect what we do.

In the future, we’d like to take out a loan, buy at least the first floor, or find investors. But no bank will give us any guarantees, no investor will risk investing in real estate that might be destroyed by shelling.

Once we build everything, we know the fairy tale of the Center for New Culture could end overnight — but that doesn’t stop us. We’ve chosen this path.

We were in fact encouraged to return to the city. We were told: ‘Come back. If you don’t make things happen, nothing will. Please, we’ll find you all the money you need’, We returned, even though we knew promises might not be fulfilled.

We looked for financing ourselves — borrowing money, selling cars, borrowing again, even from people we probably shouldn’t have. In the first year, an American fund helped us launch 6–7 showcases, which gave us momentum.

A year later, funds told us: ‘We see how much you do for the city; we want to help’. So my advice when looking for money is to knock on every door — from government and grants to large local sponsors.

Kseniia: Slava, you mentioned sponsorship money, and I want to ask you — how much do sponsors influence ideas? How much do they transform those ideas? And how often do you have to make compromises or give something up just to secure that sponsorship funding?

Slava: Honestly, it depends on their demands. All sponsors want to be featured on every piece of promotional material — and all promoters don’t want that. So it becomes a question of how much money you can attract, and how much it takes to compromise and put that sponsor’s trademark everywhere. Everyone makes that decision for themselves.

We usually didn’t put any trademarks in our design. We kept it limited to the bar — for example, you could see a shelf at the bar featuring a specific brand, and in exchange we got funding. But we didn’t go beyond that, because that’s when it starts turning into: ‘We want our logo here, and here, and also on social media’, and so on — and that’s something we just can’t allow.

ON THE DIFFERENCES BETWEEN PRE-REVOLUTIONARY AND SOVIET BUILDINGS

Anton: Building a club in a Soviet-era building versus a pre-revolutionary one, or one from the early 20th century, are two entirely different things. When you have a pre-revolutionary factory, it’s a structure with complex architecture — it was built with different rooms and spaces, with intricate connections between floors (like Closer or K41). But when you get a space without complex infrastructure, you have to build it out in a way that gives people room to explore, to walk around and to hide away. And if that doesn’t exist — you have to create it yourself.

That’s basically what we’re doing now — we’re making the space we rent more complex. We took over a venue with very few internal walls, and we’re constructing them ourselves. We’re thinking through different scenarios for how guests might behave — where they might want to spend time, what little corners or labyrinths they might want to wander through. We’re also thinking about how multiple stages should function at the same time. And we test these hypotheses every time we rebuild our space.

The main thing we’ve built so far is the walls of our main dance floor, added enough exits, and made sure that the whole setup qualifies as the simplest kind of bomb shelter and safe space. When there’s an air raid alert during an event, we basically suggest that people move to the dance floor.

We’re also constantly trying to transform the architecture of the venue and of the party itself. Our ‘main’ is fairly large, and we’re always trying to change its layout so that people who come to every event still see something new each time. We have a lot of different stage panels, and the stage architecture and DJ locations change with every event. And the lighting is always different too.

ON WHETHER THE UNDERGROUND SHOULD STAY IN THE SHADOWS, POLITICS, AND RELATIONS WITH THE STATE

Slava: I think we’re not trying to integrate into any kind of system at the state level. Instead, we’re creating an alternative to that system. Our projects offer a different vision of what culture can and should be.

Anton: Yes, I completely agree with Slava. We really want to have an influence on what’s happening in Kharkiv — but not through politics. Neither we nor our friends are interested in going into politics. We want to be an influential platform that generates ideas capable of shaping the city’s future.

We care deeply about what Kharkiv becomes — not just in terms of infrastructure, but as a community. Right now, the city has a unique chance it’s never had before: to build a new Kharkiv, even in the face of the destruction and grief brought by the war.

And I’m not just talking about rebuilding walls. I’m also talking about how we live together — about cooperation and shared responsibility. A city isn’t just its buildings. It’s a kind of social contract between people. It’s about how we coexist. So, we want the Center for New Culture to become a space that brings people together — a space that plays a role in shaping that new social contract. Right now, it’s already attracting people who care about what Kharkiv looks like in the future.

This material was created with the support of