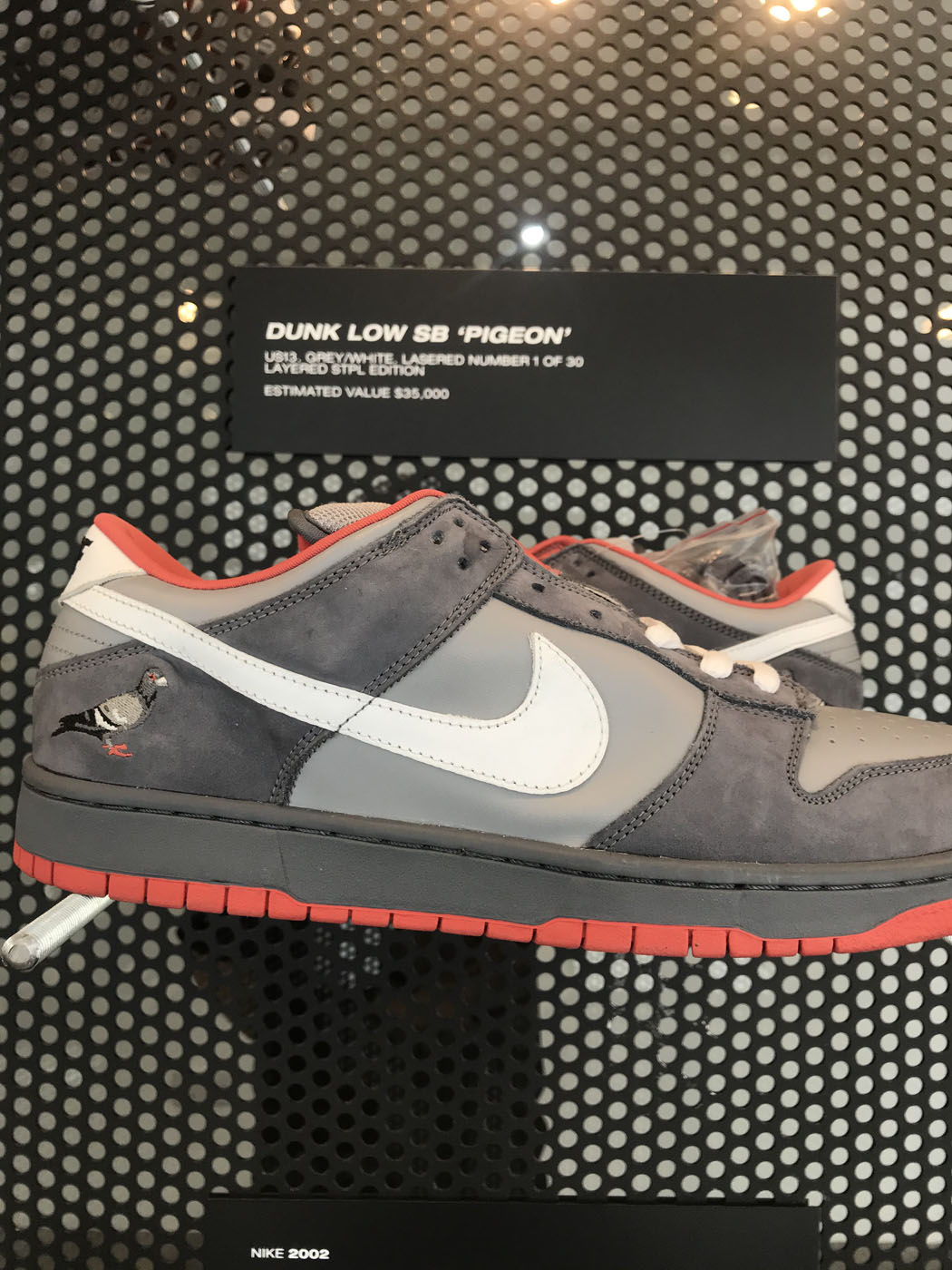

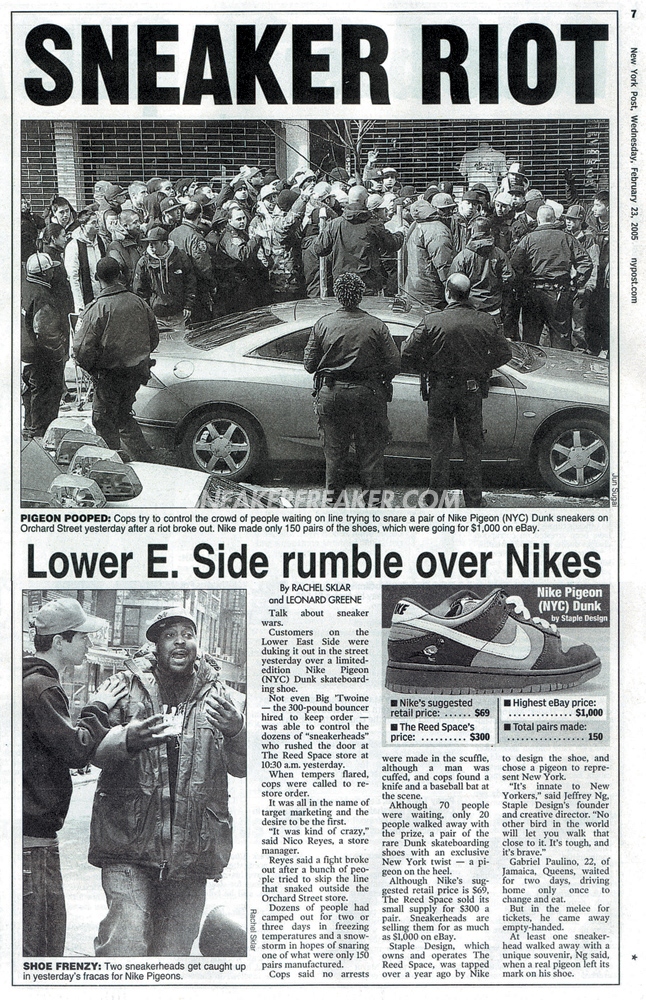

T he queue for the limited edition Nike and Jeff Staple sneakers lined up in a few days in 2005 — people came with sleeping bags, and police dispersed them due to the spontaneity of the gathering on release day. This drop made the front pages of New York publications and became a precedent that defined the hysteria around sneakers for the next 15 years, and those sneakers are valued at $35,000.

Jeff regularly produces collaborations with Nike and Medicom Toys, and he’s worked with fragment design, Timberland, Cole Haan and other brands ever since. He’s also the founder of the brand Staple Pigeon and the creative agency Staple Design, host of the radio show Business of Hype on Hypebeast, and one of the insiders and experts in street fashion and culture.

DTF Magazine caught up with Jeff at Dubai’s Sole DXB brand show and talked to him about the importance of such festivals, the nature of hype, and whether sneakers will decline in popularity

— We’re at one of the biggest brand shows in the world right now. How do you like it here?

— I love Dubai, and I come here often. I’ve been here five or six times: I’ve done a lot of shows, I’ve done a few drops. I presented the black Nike Dunk Pigeon here a couple of years ago, and I came at the request of Cole Haan this time, with whom I have been working a lot over the past few years. So it’s doubly great to come back here and support the brand.

— You’ve been to many such brand shows. How are they different?

— The main difference is the people. The visitors make the event really unique. There are a lot of festivals around the world like Complex-Con, Hypefest, Sole DXB, Maze Fest (a festival in South America) that I’ve been to, and I especially love seeing how their attendees differ. It’s nice to see street and snicker culture spreading globally.

— Which one is closest to you?

— I think Sole DXB is my favorite. It is the most atypical for me. The closest festival to me is Complex-Con, because it’s in the United States and I’m American. And Sole is interesting to me because I see a completely different part of the world here. People from Africa, India, Australia come to Sole DXB, and I get to experience other cultures.

— How important are such events for the development of the industry in the local market?

— I like to think that everything I do exists on a global level. Thanks to the Internet, the world has become super flat. If I’m doing something in New York, someone can be watching in Africa the same minute. And I don’t have to fly to Africa to explain exactly what I’m doing – the Internet is doing that. But I think there’s something else behind the information. There’s something about all those meetings with people, the handshakes, the face-to-face interaction that Instagram and other social media can’t provide. So I think it’s great to fly in to shows like this in person.

If I were in New York right now, I could watch a recap of what was going on at Sole DXB. I would see all the people, but I wouldn’t have the same feeling as if I had seen it all in person. It’s about the personal connection, the personal feeling. That’s what shows like this are all about.

— Are there any local brands that you like here? Who are worthy of attention?

— I’m sitting in a hoodie of one of them right now. It’s called Five Pillars, and it’s cool. I like to find something new. There’s another local brand, it’s called SELFI, it’s from Africa. It’s great to watch these brands and see how they develop. For example Amongst Few is a brand that I noticed about five years ago when I flew to Dubai. Back then they were making three or four T-shirts, but it’s a pretty big brand now. I mark small brands for myself, and then I follow their development, whichever country I fly to.

— How do you think they stand up to the competition in the UAE, where almost all the world’s key brands are represented?

— I wouldn’t say there’s competition between them. It’s not a competition because people can buy five different T-shirts— you don’t have to spend all your money on one brand of T-shirt. One day you want to look like a guy in Off-White, another day you want to look like a guy who’s wearing something that’s unknown to the people around him. Everybody has different tastes as well. So I don’t see it as competition, I see it as an opportunity for people to experiment.

Global brands create clothes that everyone will love. Stüssy is a great example. It’s a cool brand, everybody loves Stüssy, but it doesn’t connect directly with any particular group of people or person, it connects with everybody. And local brands connect with certain people, and go deeper into those relationships. I’ve mentioned Five Pillars before — I don’t think its founders created the brand for the purpose of «talking» to me. I wear and represent this brand, and I help get its message out beyond the target audience now. So maybe it will be global someday, too.

— By the way, I’ve seen several of your collaborations here: there are collaborations with Nike, Cole Haan, and Medicom Toys. But the media often writes that your first collaboration with Nike was the beginning of the period when people began to line up for drops. Do you see yourself as the catalyst for this phenomenon?

— No. I agree that my sneakers could have pushed it, but it could have been anyone else instead of me. I think it was a lucky coincidence, and I just got lucky. I continued to contribute to the culture in addition to my luck. It wasn’t like I only released Pigeon Dunk and didn’t release anything else for the next 20 years.

— And who or what do you think started it?

— I believe it was Hiroshi Fujiwara. That’s where it all started. Every brand did something different at first. For example, Stüssy made surfing clothes, FUBU made clothes for rappers… But it was Hiroshi, and probably a few other people with him, who saw all these clothes and decided to combine them. That’s when street culture became a global phenomenon.

— Lines for limited edition sneakers are commonplace now. Don’t you think brands are using them as a marketing tool?

— That’s true in a way. There’s a lot going on: there are limited releases, collaborations. We love shoes, we love to express ourselves, and the demand for shoes increases with the growing number of special drops and collaborations. Once upon a time, if you had 10 pairs of sneakers, you were considered weird. Now if you have 50 pairs, it’s normal, and it’s perceived very differently.

— Do you consider yourself a sneakerhead?

— Unfortunately, yes. I have about four thousand pairs of sneakers in my collection. I keep 200 in my house, and the rest are stored in different places. One day I will make a museum or an archive out of my collection.

— Don’t you think brands have begun to abuse such tools? Do you think they can give them up?

— They can do that, they just don’t talk about it. If you look at the top ten best-selling sneakers every year, there will be Nike, Jordan, Converse, but they will be basic, non-hyped models. So basically, they’re doing it, but everybody likes to talk about the high-priced stuff specifically. And brands take advantage of that because it’s marketing that makes them money. Marketing usually is an expense for big companies. They invest in it, they lose money on it. But brands make money for marketing with collaborations and limited releases. It’s a nice bonus for them.

— What do you think a hype is? What is its nature?

— Hype is a hobby. I’ve noticed that hype doesn’t just exist within the confines of street and snicker cultures. I recently went to a play on Broadway in New York City. And all the hardcore fans gathered outside to wait for the actors after the play was over. The actors were finishing getting ready, going to shower, and about a hundred people were still waiting outside for them for hours, even though it was damn cold out there. And I thought, wow, it’s like a Supreme drop line, but on Broadway. And it’s a hype too, it’s just a different kind of hype. These people were into the show, just like teenagers are into Supreme. So to me, a hype is, first and foremost, a fascination with something.

— And what and who started a hype, if we talk about its origins?

— It started with Pigeon Dunk if we’re talking about sneakers. I don’t remember anything like that before, no one was lining up a few days before the drop. If we talk about other clothes, like Levi’s jeans, many Japanese were the first to collect vintage Levi’s. People in Japan influenced that, they also collected vintage American T-shirts, which the Americans just threw away, and the Japanese made museums out of them.

— This decade is coming to an end. Can we say that hype is the phenomenon that defined the fashion industry of the 2010s?

— No, I don’t think so. I think accessibility is a phenomenon that has defined fashion for a decade. Virgil at Louis Vuitton, Kerby at Pyer Moss, and many other people like them made young people believe that anything is possible these days. It was impossible to imagine a dark-skinned man in charge of Louis Vuitton five years ago. But if you’re a teenager in college, anything is possible for you now. Now it [situations like Virgil’s appointment at Louis Vuitton] has become something commonplace. And this teenager can try to achieve that, too. I think it has defined the decade that has gone by.

— What is the role of the hype in this decade?

— It sustains interest. Hype is a service thing in general. If you learn something about culture, and you’re interested in it, it’s always worth diving deeper into the subject, learning about its origins. Because if it’s just about hype… It’s easy to tell the difference between people who are only interested in hype – they don’t care about history. And that’s okay, too.Because they’ll probably get bored with it in two years and move on to something else. What’s more important is awareness and understanding of what you’re interested in.

— What do you think of the Supreme and Louis Vuitton collaboration? Could it be considered the culmination of this decade’s hype?

— No. I think it’s something that people have already forgotten about. To be honest, it doesn’t even strike me as something interesting. On the one hand it is, but on the other hand there is nothing timeless about it. I don’t think people will be making documentaries about it ten years from now. And collaborations like Dior and KAWS or Dior and Shawn Stussy try to recreate that magic.

— What do you think will remain the subject of documentaries?

— The collaboration between IKEA and Virgil seems to me to be more meaningful. It is more innovative than Supreme and Louis Vuitton. Supreme and Louis Vuitton are like two rich people talking to each other. It’s simply banal.

— Simon Wood told us in an interview that «the popularity of sneakers is inevitable as long as adidas and Nike are fighting». What do you think about that? How long do you think this hype around sneakers, collaborations, and brands in general will last?

— As long as we wear shoes, the hype will always be there. I think it will end if only one day we invent a way to walk everywhere barefoot.

— Is hype good or bad? There is an opinion that it develops consumerism, and the market becomes oversaturated with unnecessary things as a result. What do you think about this thesis, and about the impact of hype on the fashion industry as a whole?

— There is some truth in that. But I think a hype is a way to get involved in a culture, and then find a way to contribute to it. Something good will come out of the bad. There will be people who will solve this problem of consumerism, because they will learn more about it through the hype.

— What do you think fashion will be like in the next decade? Where is it headed? Share your observations.

— Fashion is a cycle that is renewed every 5-10 years. It can be futurism, followed by vintage and retro again. I believe it will continue in the same vein.