Prune Nourry is a multidisciplinary artist, born in France. She has a degree in wood sculpture from École Boulle in Paris and explores bioethics through sculpture, video, photography, and performance. Her work involves in-depth research in science and sociology and is heavily influenced by anthropology. Among her significant works is Holy Daughters (2009), which explores questions of gender preference. Her Terracotta Daughters project began in Shanghai, and has since traveled the world, including Paris, Zurich, New York, and Mexico City; it will remain buried in China until 2030. After surviving cancer at thirty-one, Nourry created the film Serendipity (2019), which tells the story of her illness and healing, feeding back into universal questions of the human body and survival.

DTF Magazine talked with Nourry about gender selection and imbalance, the war in Ukraine and her visit to the country, and science as one more tool to understand the critical questions relating to everything that surrounds us.

— Tell me about the work you’ll show at the MOT and why you chose it. Did you know immediately what would be best to present, or did you have to choose between different artworks?

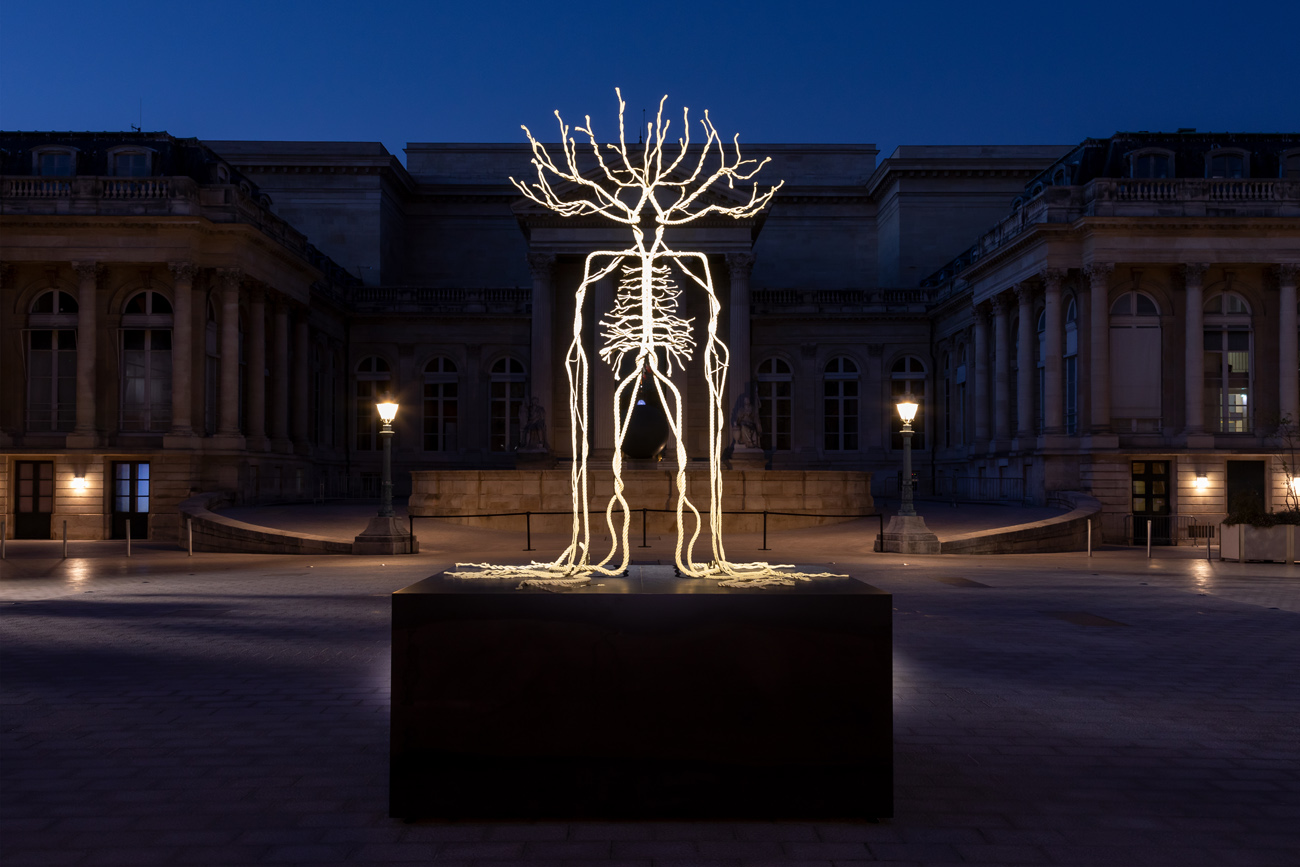

— We’ve been talking with the team for about a year, about doing a project for Ukraine. We were inspired by another artwork that I was doing at the same time. I was dreaming of doing it in Ukraine at some point, but it’s highly complex to install—it’s a 25-meter-long sculpture that we called Matir Zemlya. The idea was to build a mother with a womb, but the protective belly would be concrete, where you could hide inside like a blockhouse, a concrete bunker. When we spoke about my work being part of the show, we thought about this piece, which is inspired by the same idea of maternity and being into creation in a time of destruction.

Ukrainian women are so strong. They are also part of the army. For all these reasons, we picked that work. Matir Zemlya is universal work because maternity speaks to everyone. We all come from the womb, and it’s about protection and creation.

Sculpture Mater Earth | Photo: Stéphane Aboudaram WE ARE CONTENTS

— How did you learn about Russia’s full-scale invasion, and how did you feel about this war when you first heard?

— I heard about it from through the news and people talking. It was a shock, for sure. I feel more European than French, and even if Ukraine is not part of the European Union yet, I was sure it already was. It was phantasm or something. I’ve been following from afar with great interest—the Orange Revolution and the news along the way. To me, it was impossible news. Something you read and reread, and you don’t think it’s true. This is human craziness in action and an attack on all we care about. All the young Europeans of my generation felt so shocked and definitely connected.

— It’s strange because when my son and I came to Europe, I felt like some people were really connected to this, but it’s a very tiny group. When you stay here for a long time, people are like: “It’s not our business. Let’s talk about something happier and nonpolitical.” In Berlin, young people, I think like in Paris, New York, and other big cities, don’t feel part of it. They don’t want to hear about war.

— There is no day where I don’t speak about it, or I don’t think about it. I don’t know about other countries, and maybe I shouldn’t speak on the scale of Europe. Even if Europe is full of problems, it’s the only thing that we have against war, and we should take more care about the war being so close. We think that war is far away and something like that can’t happen to you, but then it happens. Your whole perspective and world changes. The list of your priorities shifts, and it’s not about life anymore. It is about survival. It’s so close to us that no one should be disconnected.

But it’s true what you say because when you are far away from war, you try to forget about it. After all, you don’t want to be in survival mode if you don’t have to be. It’s the tricky part. Freedom and life the way it is is not something sure and definite. If everything can change, all other perspectives can change in a minute.

I had that a few years ago with a different subject. It was a war inside my body. I had a sickness that struck me like a shock, the same way as that news. I couldn’t change anything about it. It’s that kind of thing survival mode, and you have to fight. That’s it.

Sculpture Small Circle of Life presented at the MOT exhibition in Kyiv

— Why is it essential to you as a French artist to be a part of this show in Ukraine?

— To me, it’s not even a question. As soon as the team asked me, I wanted to be part of it and be there for you. It’s the minimum; everyone acts with their weapons, and my only weapon is art. Thank you because you are giving me a way to help when I felt helpless.

— I heard that you came to Ukraine in March. Was it your first time visiting Ukraine? What impressed you the most, and where have you been?

— I went to Poland when I was a kid, but never came to Ukraine. I landed in Poland about three weeks after the beginning of the full-scale invasion just because I felt helpless. I needed to show support, to meet the artists and friends who are now working on that show, and help a little. It’s nothing. But yes, I came to Ukraine through the border with Poland border. It was the first time, and I’d like to come back.

— I hope you will come to the show. Talking generally about your practice, could you tell our readers more about your practice? Mainly, I’m interested in how you came to such topics as biology, science, and anthropology.

— My work is generally related to myths of creation, maternity, fertility, through science, anthropology, and archaeology.

It’s the mystery of the beginnings that interest me and the relation to the material. Like in so many cultures, you can find this idea, metaphor, that the human was made out of clay.For me, creation and procreation are related to the poetry of sculpture. It’s mainly because material, clay, and myths are my spine as a sculptor. It’s a way for me to express the mystery.

— So science is about finding answers to the mystery.

— I work with science especially to point out possible ethical issues like selection in procreation, for example. It seems like one of the simplest things in the world, but you cannot have a baby when you are infertile. Then it becomes the most difficult. In the old days, you would go to the temple or church to ask to be pregnant. Today, you go to a doctor, and he becomes God. In fact, your life and future are in his hands.

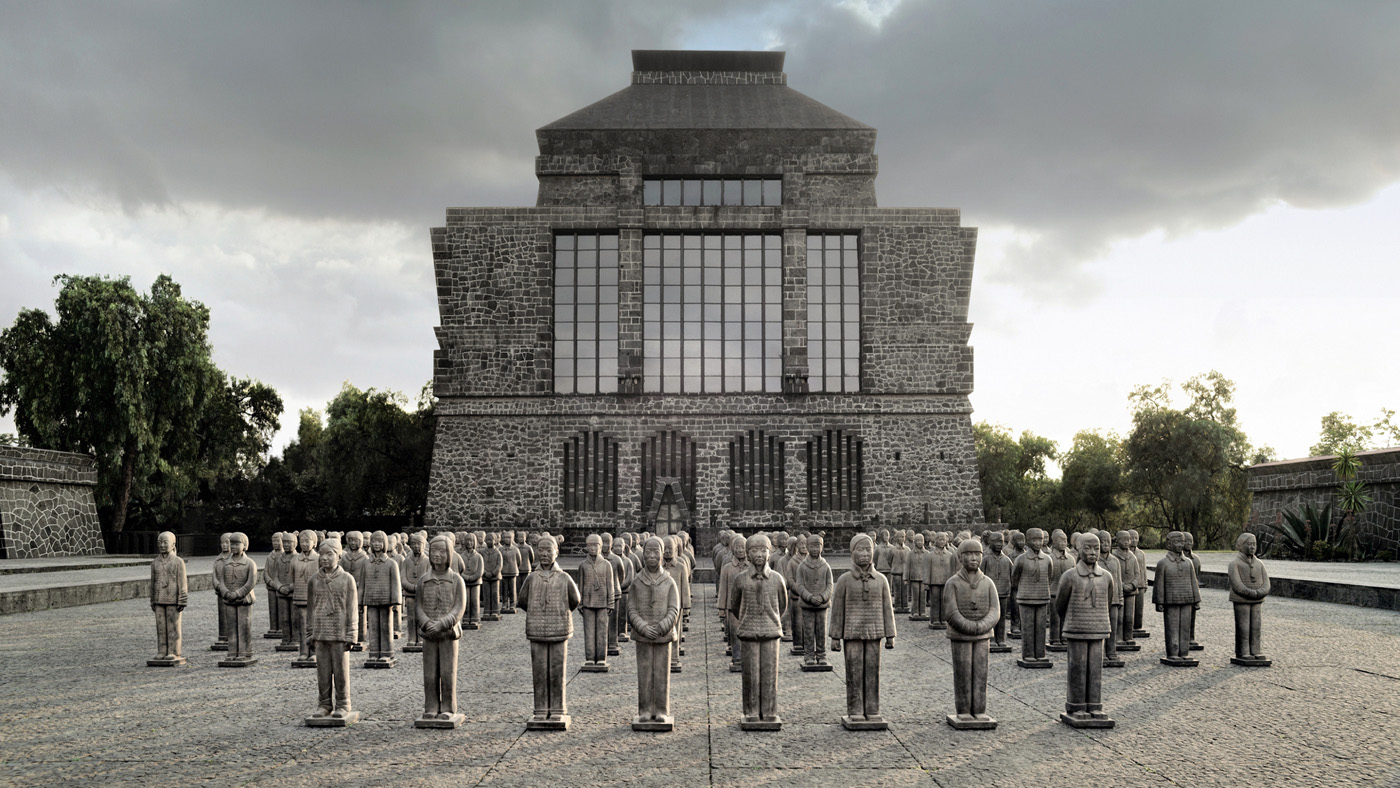

Terracotta Daughters is Prune’s project about gender selection in China. The artist drew inspiration from the famous terracotta army in Xi’an and made eight hybrid sculptures that combine the style of terracotta soldiers with portraits of eight Chinese girls.

If we can make babies through science, it is great. The danger is selection and eugenics. Gender selection has been happening since the 1980s. I’ve done projects in India and China. I buried an army of girls under the ground until 2030, in a secret place in China, about the preference for boys and the massive demographic imbalance between boys and girls. Working with Chinese sociologists, we knew that 2030 was the date when the imbalance would reach its peak. It is about pointing out the danger of how scientific discoveries can be used in the wrong way. Especially human selection: we can select the perfect baby by designing babies, but what is perfection?

The army of Terracotta Daughters. It traveled from 2013 to 2015 from Shanghai to Paris via Zurich, New York and Mexico City before being buried in China in a secret location until 2030.

— Is it challenging to work with subjects related to the female body today? Last year, we had more problems and taboos around female bodies. Even on social media and connected with artificial intelligence. How is it for you now?

— Sculpture is a different medium. It is not so direct.

It’s more about the suggestion, the poetry and mystery. It’s not like an Instagram post. Very different. The biggest question is how women have been considered and represented in art history since its beginning. This is where we should search and question.

Looking at the bodies of women in the history of art history, they’re always considered muses. When you speak about creation, you talk about Pygmalion or God making Adam in clay and Eve coming out from Adam. The creator is always male. Nancy Huston talks about it in Journal de la création.

This is not a new question. And today the Me Too revolution is pointing out and reflecting certain things that are far larger than that.

— Motherhood—how did it influence your work?

— That’s a good question. I truly respect women that don’t want to have children. They should be more considered because a woman doesn’t have to have a child and doesn’t need to want to have a child. There is something very codified about being a single woman, which shouldn’t be the case. But for me, it was a will and a need. Something I knew from when I was young. I waited for a very long time because I was afraid, as an artist, of having a kid, that it would interact with my art. In fact, I have the impression that it just opens even more the antennas and the empathy that an artist should have to function. It’s been one of the richest experiences of my life.

Sculptures by Prune Nourry

— How did the audience and art world react to motherhood as a topic in your art? For example, in Ukraine, if you are a mother, the audience sometimes reacts strangely to this, and sometimes it’s hard. We have a community of mothers working in the cultural sphere, which is a really interesting topic.

— There is still some evolution in terms of mentality that has to happen. That’s true for any profession. The fact of working as a woman and having a baby.

When I was a young artist, some people came to me, collectors for example, and they told me — “Are you sure you’ll be an artist all your life? Because, you know, if I get one of your sculptures, I don’t want to know in a few years that it isn’t worth anything anymore because you quit.” I was so shocked because, for me, art is part of my DNA. I breathe it. Quitting wouldn’t even enter my mind. I remember being shocked by these things, but then you laugh at them.

I hope mentalities are changing thanks to different experiences showing that it’s possible. It’s enriching, but I also make a real distinction between my private life and work. Of course, they are very connected, but I’m very private. I think that it is also a good plan to not mix. The kid is not your artwork.

Sculptures by Prune Nourry

— I visited the most recent Venice Biennale, where Simone Leigh and Sonia Boyce were both awarded Golden Lions. When I started to explore your works, I felt like you were talking and expressing the same things in the medium of sculpture in a positive way. Of course, not totally, but in the same direction as them, you know. What does sculpture mean to you? Why and how did you come to this medium?

I came to sculpture because, for about a year at an early age, I couldn’t sculpt, and I felt the need. I thought I was missing sculpture, so by the absence I knew I needed it. I decided to go to a very good school, focused on craftsmanship, and learn wood sculpture, to be fully focused on sculpture for three years and learn technique and then be able to go my own way. And at 21, I got that degree and started sculpting nonstop. I learned molding techniques with a Brazilian master. Then little by little, I discovered my guiding lines, my “red threads,” what I liked to do, say, and experience. I love going from one material to another.

The work by Prune Nourry. Anima exhibition at the Invisible Dog Art Center in Brooklyn, New York | Photo: Erika Hokanson

Another red thread is collaborating with the craftsman, which is one reason the material is significant. You can learn some material very quickly, but for others, it needs ten years, and you won’t even be a junior. So, if you want to work with a material you are discovering for the first time, you must work with the best artisans. Collaboration with the craftsmen is the key, especially when I do large sculptures.

Sculpture is my spine. When I see a sculpture, it’s what makes me vibrate.

Especially the one you mention, the United States Pavilion: it was my favorite because it was all about the material and techniques. I was amazed by those large fire clay sculptures. The process is incredible, which you can see in the videos they showed.

Atys by Prune Nourry | Photo: Laurent Edeline

— What supports you the most in your work?

— I’m a person who has a lot of doubt, but I’m proactive. When you take the first step, you enter into a system, an action where, at some point, you are in a wave and you can’t get out. And that’s the good thing because that will bring you to realize what you had in mind. That’s what supports me the most. To have the embryo of idea and instead of asking myself too many questions, even if I do it at the beginning, to start the movement and the energy will lead me to create what I had in mind.

Prune’s work Mater Earth will be on view in Kyiv at the MOT exhibition of contemporary art from February 17 to May 14. The theme of the exhibition is dedicated to the concept of Temporality.