Ukrainian Maryna Vroda’s debut drama ‘Stepne’ premiered at the Locarno International Film Festival. Already on August 12, the festival organizers will announce the winners, among which may be a Ukrainian film. Opinions of film critics regarding the film are polarized: from complete delight to total incomprehension. Let us tell you what film publications write about the film by the Palme d’Or winner

What the film’s about

‘Stepne’ is the story of a few days in the life of an aged man, who comes to the Ukrainian village called Stepne to care for his dying mother. Before her death, his mother tells him about a set of things buried inside the shed that ‘will revoke his memories and make him feel all those dreams he had and all those things he craved for, but never achieved’.

Director Maryna Vroda adds that ‘Stepne’ is ‘an elegiac tale with silence as one of its main characters. It is the stillness that covers the endless Ukrainian steppes and echoes in the sounds of past generations’.

Read more about the film in our article.

What critics are writing about the film

Dirty Movies

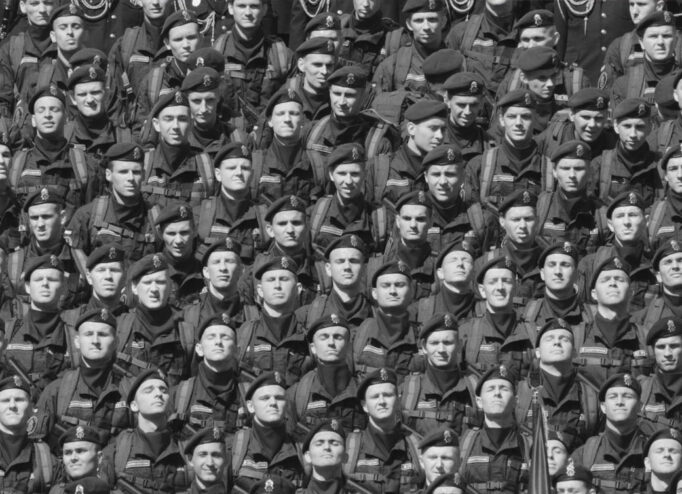

‘Stepne’ deserves credit for its realistic portrayal of a little-known face of Ukraine, and for the convincing performances (both Maksiakov and the elderly actors are honest and candid). At times, the movie feels like an observational, almost sensory documentary, a fly-on-the-wall type of register. Ukrainian director Maryna Vroda, however, had bigger intentions. She explains that ‘Stepne’ reflects upon “the silence of past generations about their history”. It takes an eye extremely familiar with Soviet history in order to grasp the inferred topics.

While I recognise that the characters are mostly silent (the conversations are sparse and laconic), I have absolutely no idea what is it that these people are refusing to discuss, and which taboos the movie is attempting to address. A woman’s choice to speak in her native Russian tongue is briefly challenged, presumably a comment on language as a geopolitical weapon. But that’s about it.

The biggest problem with ‘Stepne’ is that it fails to enrapture viewers. It possesses neither the storytelling panace nor the visual splendour required in order to keep viewers hooked for nearly two hours. Instead, it becomes monotonous roughly 30 minutes from the beginning. This is not Alexander Sokurov’s Mother and Son (1997). Maryna Vroda’s debut lacks the vigour and the aesthetic supremacy of its Russian counterpart, also a movie about an ageing son caring for his dying mother.

Read the full review here.

Universal Cinema

‘Stepne’, an enthralling motion picture presenting at the Locarno Film Festival 2023, is undoubtedly a cinematic masterpiece that leaves an indelible imprint on the viewer’s psyche. Delving into the soul of Ukrainian countryside, Maryna Vroda, portraits an astounding film of profound meaning despite its minimalistic storyline. The visual symphony that unfolds in this cinematographic narration captivates on every level; it is both pleasing to the eye and stimulating to the mind.

In ‘Stepne’, Vroda crafts an intricate narrative centered around Anatoliy’s struggle with his impending loss. It unfolds as a complex critique of not only mother-son relationships but also the human condition itself. Anatoliy, as an exemplar of stoic Eastern European masculinity, appears initially as an emotionally distant figure. However, throughout the film, Vroda gradually peels back his layers, revealing his vulnerability, his fear of being alone, and his inability to communicate his terror at his mother’s oncoming death.

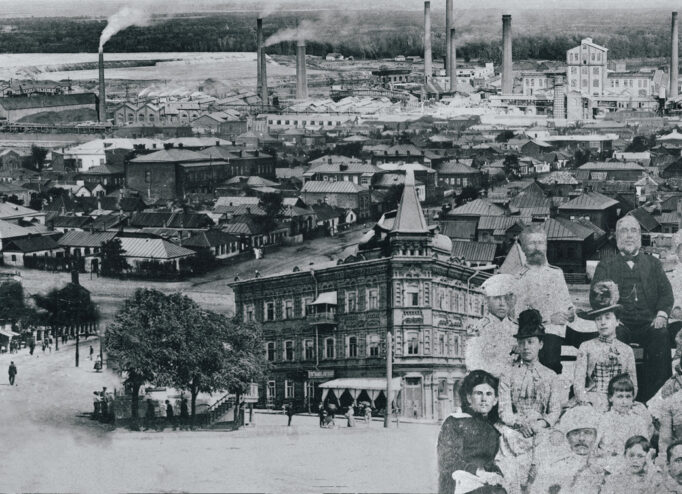

On the other side of that, ‘Stepne’ is a sharp exploration into the lives of its characters, embodying post-Soviet tropes through their personalities and experiences. Vroda masterfully articulates the broad spectrum of experiences and emotions felt in the wake of Soviet dissolution via cinematic visual storytelling.

Read the full review here.

International Cinephile Society

Location plays a huge part in what makes ‘Stepne’ such an effective piece of film. The moment we see Anatoly in the beginning of the movie traveling back to his childhood home, it already runs a gamut of feelings and emotions, and Vroda depicts all these in her takes – long and patient yet minimalist in their approach. There is a lot one can say in silence, and ‘Stepne’ thrives in these moments. In the cold, chilly outback, one can say that the town has already detached from the modern world and the isolation of the characters and the townspeople is very much felt.

The film finds its unlikely source of energy and vigor in moments when the townspeople are sharing different tales and stories. Bordering on documentary at this point, Vroda’s decision to keep the conversations flowing and let them talk about a range of topics and experiences (of war, of friendships, of humor, of survival) gives an additional layer of perspective in understanding the people from this place. While they have managed to survive all that and more, it also becomes clear that they were in a much better position then. Including non-professional actors during these scenes provides more authenticity in making these scenes work and in connecting to the audience.

Read the full review here.

ION Cinema

The entrance into ‘Stepne’ is a familiar angle, a distant, potentially estranged child forced to care for a dying parent. Vroda’s gaze is matter-of-fact, and there’s an austerity initially suggesting something along the lines of Austrian director Gotz Spielmann’s ‘October-November’ (2013). But the region and the haunted mixture of a Russian and Ukrainian community also recalls the stark deliberations of Alexey German, particularly his 1930s set ‘My Friend Ivan Lapshin’ (1985), which has more of a through line but suggests the need to examine the specificities of a certain time and place. German’s film is a period piece, but Vroda’s exercise plays like capturing echoes.

The dwindling elders, particularly the women, recall, in a much more demure sense, segments of the babushkas making doll heads in Ilya Khrzhanovsky’s impressive debut ‘4′ (2004). With crumbling Stalin inspired artwork fading away in the woods and broken stone busts slowly overrun by foliage, ‘Stepne’ evokes the words of Shelley’s Ozymandias as regards the diminished vestiges of the Soviet Union. “Nothing beside remains. Round the decay/Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare/The lone and level sands stretch far away.”

Read the full review here.

The Film Verdict

Maryna Vroda’s ‘Stepne’ , a richly lensed meditation on loss – of a mother, of ties to the land, of a traditional existence – is a melancholy recognition of a nearly extinct way of life in rural north-eastern Ukraine, a locale seemingly untouched by the Russian invasion, expiring from modernity rather than conflict. Shifting between narrative and ethnography, the film is at its best in the documentary-like sequences, which are wisely given the time to play out. Although the present war isn’t directly referenced and the events could just as easily have occurred before the invasion, the fact that this is a Ukrainian film practically guarantees a healthy festival life.

D.p. Andrii Lysetskyi (who also directed the documentary ‘Ivan’s Land’) subtly varies the visuals, at first using a handheld camera whose movements are barely noticeable but makes the scene feel like its breathing, and mixes this with fixed shots encompassing the Ukrainian landscape in early winter.

Primary colors are almost entirely absent here – apart from some light blue walls, everything is grey or brown, from the trees to the weather-beaten homes, from the clothes to the sky itself, which gives off a cold northern-feeling light. Also absent in this dying region is youth: only the elderly remain, as if waiting to die. During the wake the camera does shift to show to small kids, brought presumably by a neighbor, but their brief presence reinforces the understanding that the only way they’ll survive is to get out, like everyone else.

Read the full review here.