This year, the second most important Cannes competition «Un Certain Regard» showed «Butterfly Vision», a drama by Maksym Nakonechnyi about a Ukrainian air intelligence officer raped in russian captivity, who after her release tries to return to a normal life. The leading role was played by Ryta Burkovska. Although the film did not win any awards, foreign critics praised Ryta’s acting, calling it «magnetic», «devoid of drama and therefore even more dramatic», and «subtly conveying the state of a steadfast, unbending woman who has gone through countless trials».

This is not Burkovska’s first big role – she played in the film «Parthenon» (2019) by Lithuanian director Mantas Kvedaravicius, who was killed in the besieged Mariupol in April. However, according to her, the film went unnoticed both in Ukraine and abroad. Therefore, «Butterfly Vision» can show Burkovska to a wide Ukrainian audience under favorable conditions and the right promotion.

In addition to filming, Ryta works as a fixer and arranges interviews with the military and volunteers, and came to meet DTF Magazine with her dog Bayraktar, she took from a shelter in Bucha. In this interview we take a closer look at Burkovska, her roles and discuss the acting school in Ukraine, her impressions of the Cannes Film Festival, her taboo on roles, her desire to produce and what a film about Azovstal could be.

— What was your dream role when you first thought about becoming an actress?

— I didn’t think of acting as something I wanted to play. But I wanted to play the military. I just wanted to be an actress. Acting is mostly about how you process the information that comes to you from somewhere. It comes to you and you process it. But it’s not about me wanting to play a queen.

— What movies did you watch growing up?

— I studied at the theater department in Kyiv and we are called film and theater actors, but we never interacted with film people and we didn’t care about movies.

In 2014, I played in a short film by a director who admired the Lithuanian director Sharunas Bartas. She and I went to Odesa for the film festival. She thought I looked like the actress Katya Golubeva, and I didn’t even know who she was. And she said that we should go to Bartas’ lecture in Odesa. I went there and listened to his lecture. It’s also on YouTube. He touched my heart: it was his attitude and understanding of the film industry that touched me.

I also like Bruno Dumont [a French director working with non-professional actors («The Life of Jesus», «France» — Note from DTF Magazine], Andrzej Zulawski [Polish director born in Lviv («The Devil», «Fidelity») — Note from DTF Magazine], Kim Ki-duk [South Korean director interested in questions of the soul in films («Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter… and Spring», «Pieta») — Note from DTF Magazine].

— Did you get any benefit from your university education?

— I had great teachers, but the course was russian. Today we can understand that russian culture was imposed on us.

We didn’t have movies in Ukraine at all — nobody was making them. The center was in Moscow and you had to go and shoot there if you wanted to make movies and a career.

My teachers did great trainings. Thanks to some of them we got to know Anatoly Vasilyev’s theater. And we got a cool experience from Oleksandr Khryzhanovskyj, who works in Pecherskyi district. It was a powerful encounter because he taught us how to play themes – he taught us not to put on a character, he taught us techniques and how we can explore life.

There is a cliche of how to play about love, and he was offering us ways in which we can detail some things, combine something. For example, colors or a word express something. You can play a breakup scene, but not a love scene where you go on stage and show a person in love. He was developing us. I have nothing to complain about. But the only thing I had to forget was the russian language and diction. I stopped doing it because I don’t think it’s necessary in filmmaking.

— How do you feel about the literary Ukrainian language and surzhyk in Ukrainian cinema?

— As far as I remember from Valentyn Vasyanovych’s interview, he would like to avoid surzhyk, because he is tired of it. He doesn’t want to present himself through surzhyk. I don’t speak surzhyk either, but there are plenty of people who do. But why only surzhyk? It’s very hard for us to get close to a living language. And movie people do it from different angles.

Natasha Vorozhbyt uses surzhyk because she sees it and it is easier to reproduce it in life, and we don’t use difficult constructions. Cinema has to be authentic. For example, I became fully Ukrainian-speaking two or three years ago. I had some attempts to switch to Ukrainian during the Maidan, but it was a volitional attempt.

— How would you describe this attempt now?

— It’s complex. I grew up in a Ukrainian-speaking family. We bought a house in Cherkasy region 150 km from Kyiv and we had a dacha with a garden there. My great-grandmother spoke Ukrainian, so that’s my roots and understanding, and I studied in gymnasium №178 when I went back to Kyiv. She was russian-speaking and it was a shame to speak Ukrainian there because it meant you were from the village and you were second-class citizen. This is very powerful propaganda.

At school it was considered that your native language is the one you think in. Then I thought in russian, but even as a child I said that I didn’t feel that russian was my native language. I have a connection to the Ukrainian land, to the language.

It was the same at university — we had popular jokes about the Ukrainian language and literature. It was always thought that Ukrainian literature was primitive, that it was about a palianytsia, a beggar, oxen, etc.

Language is a different mentality and meanings. When you read literature at university, you might get the impression that Dostoevsky is a cool author, a carrier of ideas, but Lesya Ukrainka is about flowers in a field, but this is not true, because if you study the literature, you realize that they are different in symbolism.

We are bearers of another culture and cannot play as in the Soviet theater, as Stanislavski taught. We don’t need this. We need Les Kurbas, who thinks in symbols and plays differently.

— What’s your dream role?

— I like movies that contemplate life. I like the ideas I discover in meditation because I do it a lot and do reiki. That’s how I explore a lot of things. For example, suffering is the ego.

I don’t want to play a character who affirms suffering. It would be cool to convey and broadcast that one doesn’t have to suffer even if the character is going to be in a difficult situation.

A person can experience difficult situations. I really admired war photographers, people shooting in war. Now I’m a bit of a fixer and I would really like to play a character with that profession.

— Two of your roles in feature films have a social component in one way or another. And they are dramas. Is that a coincidence or are you really interested in those kinds of roles? Would you like to work in other genres and which ones?

— Genre is a director’s way of thinking. For example, for me, Tarantino is one of my favorites because he makes films about heroes. He has archetypes, but he mixes genres, he can add interludes. It’s an action movie, but not a simple one.

I’m friends with irony, I understand it, and I can do it. However, I would like it to have interesting content, to have a deep story. For example, the good guys killing the bad guys in the movie «Inglourious Basterds». There are a lot of funny moments, but to me it’s a heroic movie.

«Life is not divided into women and men»

— Maksym Nakonechnyi tells the story through his prism in «Butterfly Vision». And after all, it’s a man’s prism. How does this point of view affect your work?

— Life is not divided into women and men. This is not the case even among soldiers. It’s clear that I have a different body, needs, psyche. We are different, but in general I don’t see the point of focusing on this. If a person is whole, he perceives both the masculine and the feminine in himself and in others. If people make jokes about it, they are dumb and limited. It’s ok if Maksym wants to make a film about a woman. He doesn’t have to be a woman. And he doesn’t have to have a traumatic experience to make a movie.

Читайте інтерв’ю з режисером «Бачення метелика»

Максим Наконечний: «Хочеться бути суперагресивним, але не варто»

— And why was Mantas so drawn to the subject of Ukraine in movies?

— I don’t think he was drawn to it. He was an anthropologist, a very smart and intelligent man, he had an interesting way of thinking. He had an interesting way of observing life. He studied the nature of people and the world, for three years he filmed Chechnya, how the FSS kidnapped people, tortured them, sold their bodies to their families. There was no one to make this movie. He went to Mariupol to film when the war started in Ukraine. Mantas told me that he wasn’t afraid to film at all then, and then he made the decision to go there again. As far as I understand, he was detained, tortured and killed. There was a version that he came under fire. That is not true. But they know by name who tortured and killed him.

— Hanna Bilobrova played a Ukrainian sex worker in his film «Parthenon». And now there are a lot of reviews on the net about how the world sees Ukraine, particularly in a negative context, saying that criminal gangs and illegal prostitution are prevalent here. Do you feel like you could play a sex worker after there have been more of these accents?

— I was once offered the role. It was the role of a sex worker and I turned it down. Mantas also offered me that role in «Parthenon». It’s not a role for Hanna Bilobrova. We could have combined storylines, but I said «no» at the time. At first I had the lead role in «Parthenon», then everything was re-edited. When he and I met, we were both in Athens. And it’s a cool port city, there’s a lot of graffiti, different people from different countries and refugees live there, I was struck by drug addicts who were shooting up right in the street, brothels and Greek antique culture that was around all that. I think his main theme was the exploration of the individual in certain circumstances, his nature, rather than the theme of sex workers and specifically Ukrainians.

— How do you think Cannes audiences took «Butterfly Vision»?

— Before I went to Cannes for the premiere, I worked as a fixer in Kramatorsk, and even before that I went to Bucha where we were in overcrowded morgues, saw a father digging up his son, a mother tying a handkerchief to her son’s leg so he wouldn’t get lost in the morgue. When you’re away from something, you construct reality, and when you’re near it, it’s a little easier. When we stopped by Sievierodonetsk and interviewed people under fire, they said they weren’t going anywhere. And we only saw Cannes after that. For me Cannes is beautiful.

We need to talk to journalists to form the right messages and meanings of what is happening here, to provide timely information, financial and armed assistance, to record war crimes.

It’s great that there’s Cannes, where people dress beautifully, change outfits three times in one day, drink americano and Rosè — I’m not offended by that. I’m not lazy to repeat a million times why we need to put russian culture on pause. The only issue is that they don’t really get it.

The most important thing is the press for the movie. I just had a bad experience with «Parthenon», so I had no expectations about «Butterfly Vision». I think it’s a very powerful and talented film, but it went unnoticed. No one saw it here and there. It was the most powerful when we screened it at the film festival «Molodist» program. So when there’s a lot of press around «Butterfly Vision» at Cannes, I compare and think it’s awesome. I treat it like a job.

Читайте також:

Одяг як висловлювання: Розбираємо протестні образи команди фільму «Бачення метелика» у Каннах

The institute of meanings and taboo on roles

— What do you think of the institution of stars in film festivals, especially in Cannes? Is it something we should strive for or is it something we need to move away from?

— I think we should organize this institute. It’s a very cool story, but it would be cool to organize an institute not of stars, but something with certain meanings. Most of our Ukrainian media is focused on the russian view in culture anyway. But we have a new talented generation that is capable of reflecting on the events that are happening to us all.

— Could this new generation be an export for Hollywood?

— It depends on what we’re talking about. If Tarantino comes here to film and I’m known… How does it happen? He comes and looks for an actress. He’s told, for example, that I’m famous and he says yes. It would be different in the case of Mantas or Bartas .

— Do you have any taboos about scenes or even whole roles?

— Regarding the scenes, I’m not so sure. I won’t kill animals. I don’t have taboos on roles. I won’t play a Ukrainian woman in a brothel in Poland. Or I won’t play a girl from the NKVD (the People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs).

— Would you be able to play a russian woman in a pro-Ukrainian film? You have actors in «Butterfly Vision» who play occupiers.

— Yes, we had a great volunteer from Slavyansk who helped us and the city a lot in the film. I would play that role if there was a great idea. I don’t like getting into another person’s skin. Someone at the premiere came up to our actor and said: «Wow, you’re unrecognizable in person and on screen». And I was reminded of the fact that the actor must get into another person’s skin. But I don’t follow that belief. You have to open up and be yourself as much as possible.

Producer ambitions and reflection on PTSD in the film industry

— What would you like to do besides acting?

— I would like to try producing. But there are different kinds of producers. As a matter of fact, I’m doing a little bit of that now, too, which means I don’t just offer journalists to call and meet and do interviews. I can offer some story because I understand the context of events. I understand about Azovstal. It is important for me to keep the focus on people. We understand that there is a different Mariupol even at this time. There are people who are waiting for russian soldiers and who are «out of politics in general». There are people who took up arms, prepared for this war and defend Ukraine. They were at Azovstal until the end. I understand that many people will make films about civilian people, war crimes, but I have an understanding and an idea that I can offer, so it’s already a producing job.

— Does that mean you’d like to produce a film about Azovstal?

— Yes, of course. But I’d like to do it as a creative producer: I’d like to look for money, put a team together, find meanings. I don’t understand much about producing, but the basic thing is to get a feel for the idea and push the idea.

— It frightens me that films that are monuments to tragic events can be quickly forgotten. Such was the case with «Ilovaisk 2014. Donbas Battalion». Would you like such projects to be not only memorials, but also a reflection of these events?

— I wonder what we call culture. People still think of it as singing, dancing, and cross-stitching. Culture is a much deeper process in which we participate. For example, it is a culture of memory.

We have to rethink a lot of things, to deal with facts. So culture is an ambiguous layer, because it’s not always about the artist. Society believes that culture is dancing and singing, and that culture should be good. I want people working in state institutions to be from a new formation.

We have a big heritage that we don’t interact with. It’s only the Dovzhenko Centre and the Ukrainian Cultural Foundation, as far as I understand. But it’s hard to do a project about stress disorder at the UCF because they don’t think it’s about culture. But it’s about culture, because culture doesn’t keep something quiet — it’s also culture.

When people say that a hero from Ilovaisk or Azovstal should be made with a Soviet «template», the artist will investigate life, meet these people, and he must show a vision of the event that is unique to him. That would be artistry.

— Your character has PTSD in the movie «Butterfly Vision». In Ukraine there are different understandings of this experience. In particular, there is a contradictory immersive situation when it is suggested to convey the experience of a Jewish Holocaust survivor through the «Babi Yar» memorial. How do you think such experiences should be conveyed?

— I have read that PTSD is the kind of trauma that is not identified as an illness. The professional literature suggests that a person is capable of adapting to certain new information processing abilities. Not everything that traumatizes us is called PTSD. It has to be something extra. For example, people are now in Lysychansk, Izium, Kherson. If a person is constantly under stress and in a life-threatening situation, this syndrome can develop.

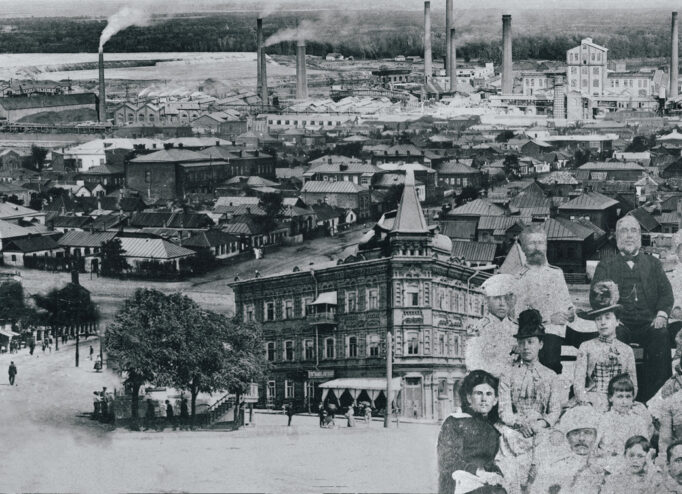

If we talk about movies, it’s always about scale. Situations that change a person happen nearby. For example, Vasyanovych doesn’t put PTSD at the center of his character. He shows the scale of the land of Donbas, namely the factories, the lava, the colors. His man is included in a process that is larger than this man, and he shows this in big plans. My character Lilia in «Butterfly Vision» is not separated from the process. That is, there is no task to put her in the center.

We are all traumatized, just some more and some less. But we can adapt, be effective. Now many people are afraid of war, but this experience can be rethought and something new can be gained.