On May 5th, the Ukrainian drama Pamfir will be released in Great Britain. It is a story about a good family man who committed a crime related to smuggling for the sake of his family. The events of the film take place during the Malanka holiday and were shot in 2020 in the Carpathians. The film was first shown in Directors’ Fortnight at Cannes.

Nikita Kuzmenko, cinematographer of Pamfir, received an award for this work at the Raindance Film Festival in London. However, he shoots not only Ukrainian films, among which, in particular, Let’s Dance, The Living Fire and Vodurudu. Nikita worked as a cameraman of commercials for Dior, PUMA and Oakley brands, and shot music videos for Harry Styles, The Weeknd, Foals and Rosalia.

DTF Magazine asked Nikita about the Carpathian Mountains in Pamfir and the best film in 2022, as well as why he believes that he received a quality education at Kyiv National I. K. Karpenko-Karyi Theatre, Cinema and Television University.

— How do you feel about the fact that people watch large-scale movies on small screens?

— In general, it’s okay to watch a movie on any screen, as long as, when watching it, you stay focused and feel the magic the author has put into his film. It’s everyone’s own choice, and there are times when people don’t have the opportunity to watch some interesting film on the big screen. It all depends on everyone’s capabilities and preferences.

I prefer movies that require concentration and my inner presence while watching them. I think it’s better to watch such films on big screens and with good sound, because that’s what the authors had in mind. You can’t feel the moment when the light turns off and the journey into history begins when you watch the film on your phone or tablet. This year I attended the Cannes Film Festival where we presented Pamfir, and even though my team and I watched the film on the big screen when it was ready, it’s impossible to compare the moment of the premiere with anything else. It was a fantastic experience and very strong emotions.

In fact, it’s already a privilege to watch it on the big screen. I had the opportunity to see the film Decision to leave (2022) during the premiere and it was incredible. The screen was amazing and the atmosphere here was such that I understood why everyone wants to go to Cannes. It’s really cool and emotional. You realize it’s movie magic here. When there are no lights, you don’t get distracted and you can concentrate. Cinema is about concentration. But the modern world is so fast — social networks, cell phones… And it’s not always convenient to watch a movie on your phone because someone is texting you all the time. I sometimes watch series on the small screen, even though I don’t like them.

— Don’t you like their episodic nature?

— I guess so. I usually miss cinematic language and some interesting authorial visual decisions. But that’s not totally true, because there are more and more interesting series coming out, and their creators already know how to do cool things. I try to watch all the hits that come out, but there are a lot of movies I haven’t seen, although whenever I have time to watch something, I choose movies. Watching TV series is a secondary thing for me. I get less inspiration from TV series than from movies.

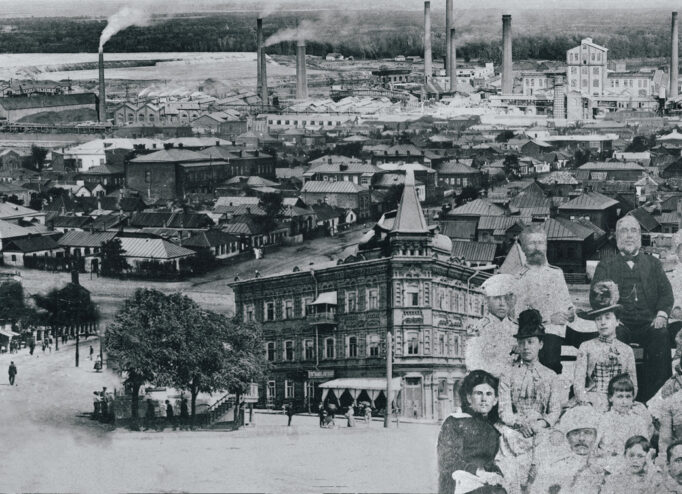

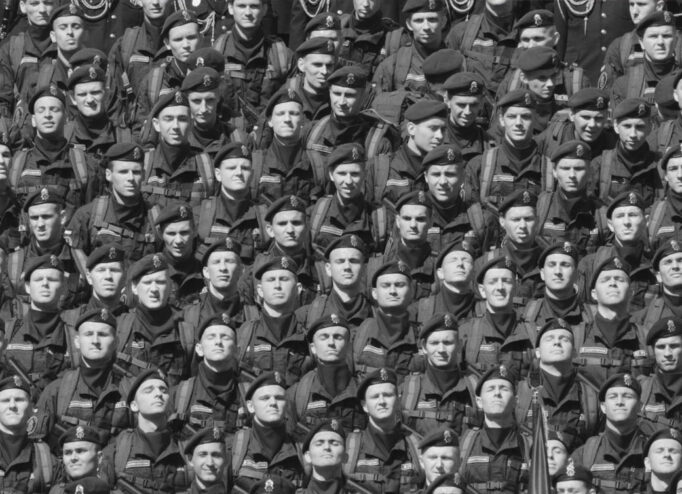

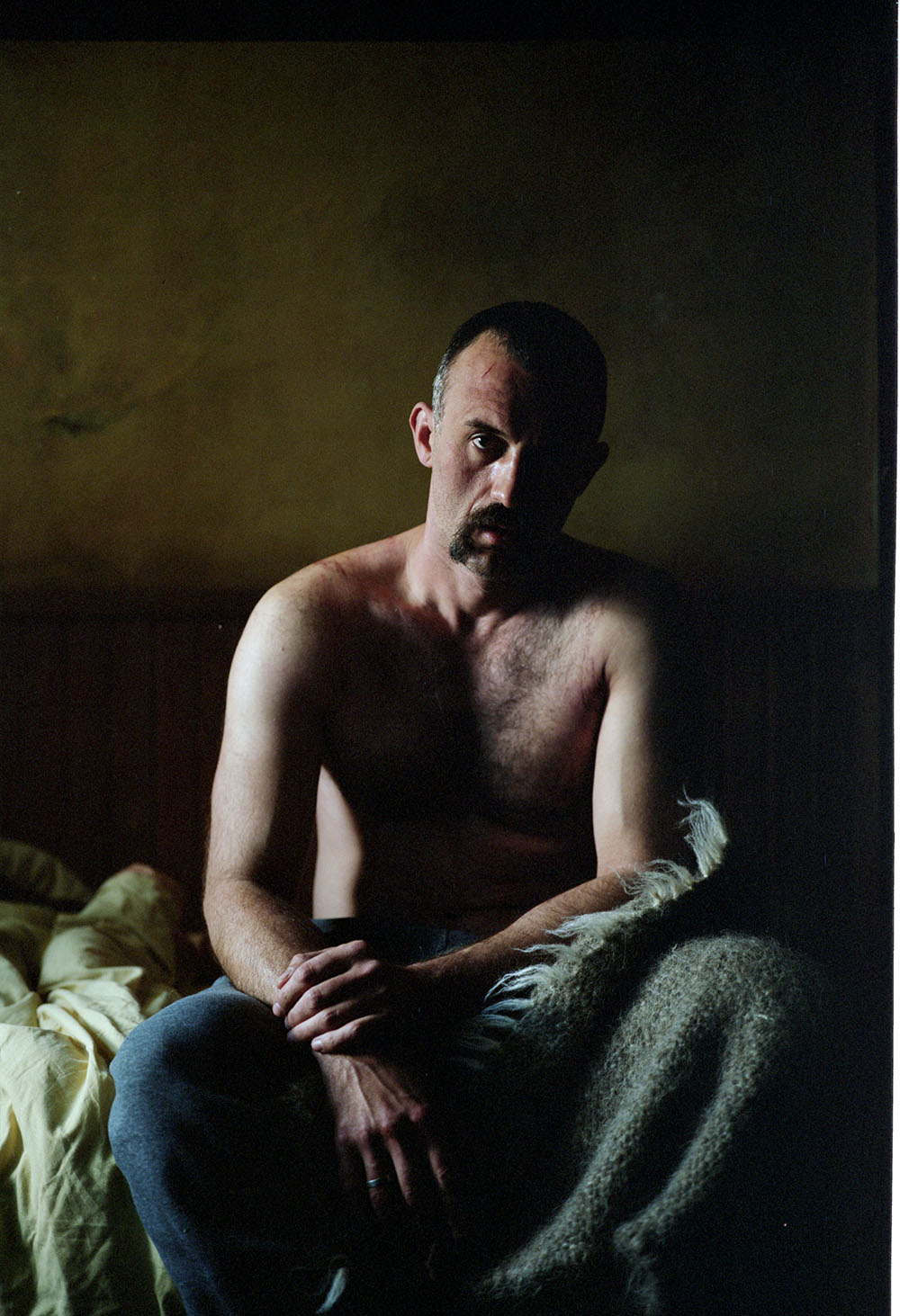

On Pamfir set, from Nikita Kuzmenko’s archive

— What interested you in working on Pamfir?

— I must begin by saying that the Pamfir script is probably the best script I have ever read. I very much hope that someday the audience will be able to read it as well. In fact, this text was the starting point for me, because when you read it, you realize how perfectly the scenes and setting are thought out at the script level. It was also complemented by the director’s storyboards, concept art, location photos, and cast. It all made a big impression on me and was very inspiring because I was finally able to imagine what the film would be like. The answer was: yes, I want to be part of this project.

Me and Dmytro (Sukholytkyy-Sobchuk, director of Pamfir. — Note from DTF Magazine) worked together almost 10 years ago, back in university days, and created a rather complex project together, Roots, so I had a clear idea of how serious he was about making his debut film. After analyzing all the information about this project, I realized that this was exactly the kind of film I dreamed of making at the time. In short, a lot of factors came together in the blink of an eye.

I don’t like to persuade people and I don’t like it when someone persuades me. When it comes to creativity, that’s the last thing I want to do, to persuade someone, to waste my energy.

I understand that if it’s a collector’s work, you can treat it differently. That’s where the other side of the business works, and in film it’s important to have an idea and an energy interaction with people. You have to feel that they are right for you.

On Pamfir set, from Nikita Kuzmenko’s archive

— After The Living Fire, Pamfir is your second project related to the Carpathians. At the same time, it’s also a great place for filmmakers from other countries. In particular, Zhang Yimou filmed House of Flying Daggers there. What do you find so cinematic about the Carpathians and what do you consider cinematic in general?

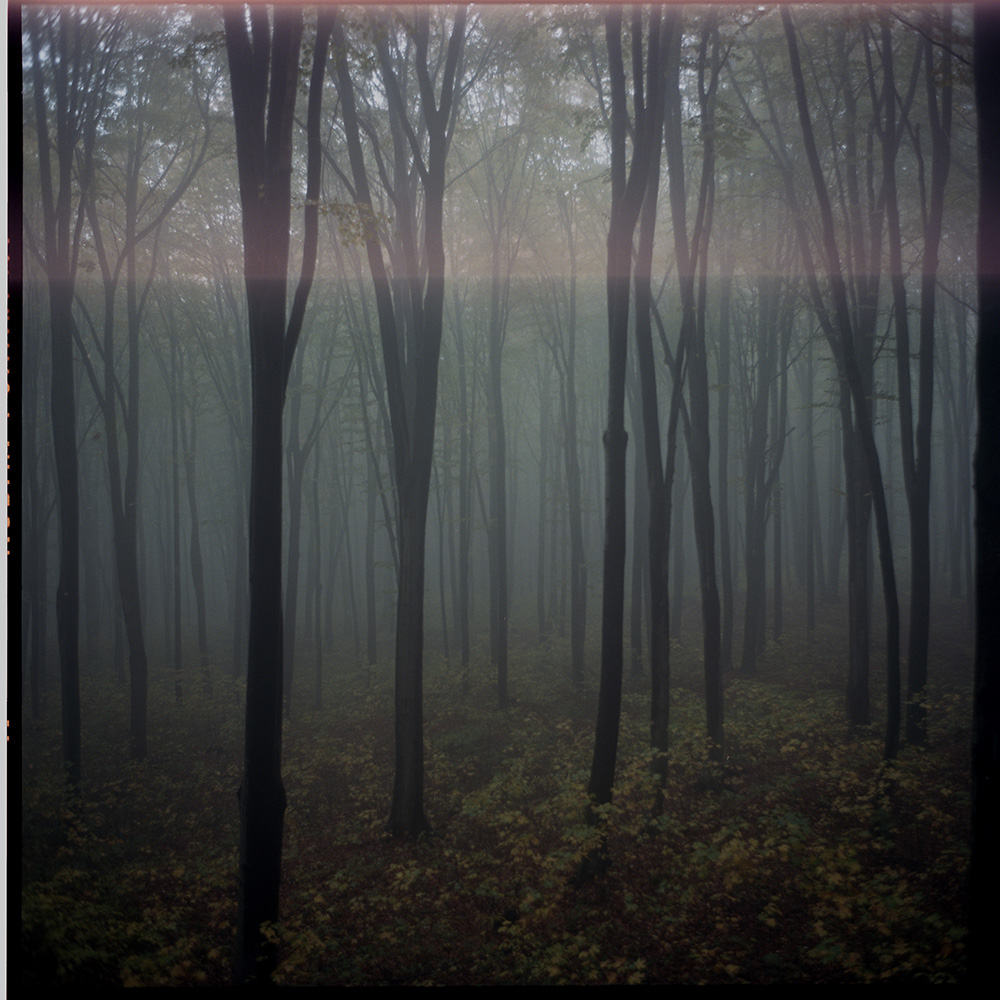

— For me, cinematography is about energy. If we talk about cinematic locations, these are places with powerful energy. The Carpathians have culture, history, nature and incredibly interesting people. With the multifaceted world of Pamfir we were able to combine this and show the viewer the region from a feature film perspective.

It just so happens that I choose creative projects. My concept is that in scripts I look for the energy that resonates in me. The energy depends on the actors and the film language that the director wants to create and on the way in which he wants to tell the story. For me, it’s the energy of the space and the way the director puts the idea into that space. I’ve already filmed The Living Fire in the Carpathians, and it gave me a great experience for Pamfir, and now it’s every filmmaker’s dream to film the Ukrainian Carpathians.

Pamfir is the benchmark for what filmmakers would like to shoot in the Carpathians. There you can reveal the theme of people and authenticity more widely. It’s a rare case when such a scenario combined with the Carpathians. I don’t even want to think about what happens next. I will gladly wait for the filmmakers to make something new about the Carpathians.

— The movies Klondike and Bad Roads show Ukraine from the other side — they show its steppe zone. Are you interested in working with such a landscape?

— Of course! I am inspired by nature in my work. But if you look at it from a cinematic point of view, what matters is the story and how the director wants to tell it. I like a complex simplicity where there is minimalism in the space, backed up by complex dramatic and technical solutions.

I could have potentially participated in ‘Klondike’ and ‘Bad Roads’. It so happened that I didn’t shoot them, because at the time I wasn’t ready to make a movie that raised such difficult and serious topics.

Although, of course, I considered these proposals and talked about landscapes, thinking about them. In fact, I don’t think it makes any difference where to shoot. But there is something in the Carpathians that magically attracts me, something that is not present in other mountainous areas of the world. I haven’t felt this energy of place anywhere else. I’m not a minimalist when it comes to the world in which history unfolds. I thought about landscapes again after your question, but when I shot Pamfir, I didn’t think about them. You know, the creative consciousness comes later.

— Are you reflecting on your old works?

— Yes, I love to rewatch old works from time to time. I remember many moments related to the periods when I shot them. The picture you’re looking at (the light, the composition, the camera movements, the atmosphere) is a kind of reflection from the past. Self-reflection is about looking inside yourself and your thoughts, remembering your attitude to the picture at the time and actually comparing it with the one you have today. After that, questions about the future arise.

— What Ukrainian film would you like to make?

— All the films I wanted to make, I made. Each film I work on is a different page of my life. Choosing projects is always a very deliberate process. Many factors influence whether or not I will make a film, so maybe I would like to make a film — given what I’ve already seen of the result. I don’t know if I would have wanted to work on it at the time it was offered to me. I watch my colleagues’ films and I’m always very pleased with the experience they’ve had and have been able to convey through the screen.

My first film Let’s Dance came out in 2015. Then I took a break and did not take a full part in the Ukrainian cinema. I only made the short film MiaDonna with Pavlo Ostrikov, and I didn’t make anything else, because I wanted to learn something so that I wouldn’t have to resort to cinematographic self-deception.

What’s the point of making a movie that’s just beautiful? You have to make something that tells us something. That’s why I choose projects that affect me, excite me, and can help me talk about my emotions.

I’m working on finding the fine lines between my own consciousness and emotionality, and on figuring out how I can reconcile them. I’m learning to work with future technologies and with myself.

— Do you have the same approach to working on a music video and a film?

— Of course, the specifics of working on music videos and films are different, but in terms of details and how the preparatory and filming process takes place, everything remains the same. I just have to creatively adapt to specific conditions, but in general as a personality I remain myself.

In film there is a little more time for some things, but the responsibility is the same, so the attitude doesn’t change. It is important to feel what you are working with. This is what keeps you from relaxing while working on a project, but instead encourages you to set yourself tasks and solve them. When this becomes a habit, the level of mastery begins to grow.

When it comes to the Western film market, I have met many cameramen of different levels. They all shoot movies, commercials and music videos. Darius Khondji (cameraman of David Fincher’s Seven and Alejandro González Iñárritu’s Bardo. — Note from DTF Magazine), who for me is a cinematic icon in cinematography, shoots commercials with young music video makers. His style matches that. He’s a modern cinematographer even though he’s many years old.

On Pamfir set, from Nikita Kuzmenko’s archive

— You graduated from Kyiv National I. K. Karpenko-Karyi Theatre, Cinema and Television University and in one of your interviews you said that you would like to go back to the time of your studies. Why do you like the period of your student years and what did your Ukrainian education give you?

— I’m all for education. Especially for cinematographic education. Probably because it allows you to concentrate on your creativity. You’re surrounded by people who have the same dream as you — to make movies. Among these dreamers, you might find exactly those with whom you will create movies in the future.

My teacher at university was Bohdan Verzhbytsky, an incredibly talented cameraman and a very kind, polite man. His films still inspire me to this day. He created such an atmosphere in the group and chose the way of presentation of the material that allowed me to fall in love with the profession. This is the most important thing that gave me an education. I am infinitely grateful to him for his dedication and the time he devoted to my group.

Yes, it was a difficult period. Digital technology had just begun to appear, and we were shooting on film. I still study cinematographic art, and I often remember what we did at university. The teacher gave us the opportunity to watch films and write camerawork reviews, that is, we analyzed camerawork in detail, because analysis helps cameramen. Now I rewatch films by, for example, Krzysztof Kieślowski, and I think: what could I have understood back then, in my university days?

Dmytro also graduated from Kyiv National I. K. Karpenko-Karyi Theatre, Cinema and Television University, and each of us had a different experience. I was 18 years old, and they literally ripped off my childhood skin, exposed me, and taught me cinematographic art — without any concessions or indulgences. It certainly could have been traumatic for a lot of people, so I won’t deny that they must change something about their attitude toward students. But overall, I have positive and vivid emotions about the university.

On Pamfir set, from Nikita Kuzmenko’s archive

— Then you moved to Poland and studied at Wajda School. What was that experience like?

I got into the fellowship program at Wajda School while working on a documentary filmmaking project. At that time my motivation was as follows: I graduated from Kyiv National I. K. Karpenko-Karyi Theatre, Cinema and Television University, but I didn’t feel the dynamics of progress. I wanted more experience, so I started looking for a place to study abroad. I found a scholarship program and prepared for it. It wasn’t easy, but I was accepted. I studied in Poland for half a year but I didn’t make my film. It stayed on the shelf, but something different happened.

I read LJ (online platform LiveJournal. — Note from DTF Magazine) by Oleksandr Pozdniakov, who by then was already studying at the film school in Lodz and at the same time was working on the The Living Fire project. Together with the director and actor Ostap Kostyuk, they traveled to the Carpathian Mountains and conducted research. One day he invited me to join them, and I went with them to take pictures. From then on, we filmed this movie together.

So, my experience in Poland was very important and motivated me. I spent most of my time with students of the film school in Lodz, helping them shoot student works, gaining experience, learning languages, and making a short film. When we started shooting The Living Fire, I returned home to Ukraine, and a new phase of my work began in 2014.

— Whose works inspire you and which ones do you try not to watch so they don’t affect your style?

— Lately I prefer auteur cinema, where I look for interesting young authors. If I can, I visit museums. This year I saw Munch in Paris — and it brought me to tears. But the main source of inspiration for me is life.

On Pamfir set, from Nikita Kuzmenko’s archive

— You are the first Ukrainian who won the MTV Video Music Awards in the Best Cinematography nomination. How important are the awards for you?

— Awards open up new opportunities, and festival participation is an important part of the industry. However, I can’t say that this is important to me. There are many other topics and issues that concern me. It is a pleasure to receive the awards, especially now, because they are related to Ukraine. They are all dedicated to my teachers and friends who taught me so much about the profession.

My inner goal was to remove the conditional barrier so that we would be on the same level in the music video world with the Americans, the French, the Germans, and the British, that is, with the nations that are considered cool. And that has finally happened. People treat you differently when you say you’re from Ukraine. It immediately makes you better in their eyes, even though you didn’t study at the most expensive school in the world, only at Kyiv National I. K. Karpenko-Karyi Theatre, Cinema and Television University. When I received the award for Pamfir at the most prestigious film festival Raindance in London, I was proud of my country because I took the prize to Ukraine!

— After so many collaborations, who else would you like to shoot with and for whom?

— Visually, I am attracted to East Asian cinema, including Japanese cinema. It’s different from what we’re used to seeing in European and American cinema. It’s this “difference” that attracts me the most, so when I watch new projects, it’s important to me that they be original and not like the others.

If Park Chan-wook asked me to direct the next film, I wouldn’t turn him down. If we’re talking about art it’s Munch, if we’re talking about film it’s Decision to leave (2022). We still look at Asian films through a different prism, because we don’t understand the original, but there are deep subtexts. Just as there is in Pamfir. Pamfir is also rooted in Asian cinema. Dmytro once said that this film would be the most understandable in Ukraine. I’ve seen people overseas watching it. It takes foreign viewers a second longer than it does for us to understand what is being said in that stable about God when the cow gives birth.

I want to tell stories that reflect my inner state. I don’t care if there are fifty films in my career, as respected cameramen have. I’d rather have ten or fifteen films, but so that when I watch each one I can say to myself: “What an adventure!”

We recently finished shooting Pavlo Ostrikov’s U Are the Universe. It’s a great film. It’s a powerful story about people’s lives and country — with humor.

— Were you outraged about anything regarding the cinematography nomination at this year’s Oscars? Analysts say Hoyte van Hoytema should be nominated for Jordan Peele’s Nope.

— I can’t say I was outraged by it, but I was surprised that there were no other camerawork hits in this category. It’s good work that’s technically on another level, but the film didn’t really impress me.

And Top Gun: Maverick (2022) was not nominated for best cinematography. I’m not into Jordan Peele’s work, that’s why I didn’t like Nope (2022). The title of the film coincides with my feelings about him. (laughs) However, from a purely technical point of view, it’s brilliant.

New opportunities open up for you if your work has been nominated. You are invited there to win another Oscar. I already have experience and a clear idea of how the world of the film industry works in this direction. There are serious political games here.

The problem is that we start watching content because of the number of awards it has received. Awards, of course, push us to choose this or that film, but we should first of all look for information about the authors and be interested in them. It annoys me that awards sometimes make hits of things that aren’t hits. At Cannes, I heard a lot about Triangle of Sadness (2022), but you should definitely watch the other films that were presented at the festival. I, for one, suggest everyone watch EO (2022). I think it’s the best film of the year.

On Pamfir set, from Nikita Kuzmenko’s archive

— Are you thinking about making your directorial debut?

— I’m moving in that direction because I see myself not just as a cameraman. There has to be a story I want to tell, but I don’t write, so that’s the main obstacle. When I was making short films at university, I was inspired by the visual impact of space. Directing is very complex and needs many other skills, so I am slowly improving my knowledge related to directing. By making movies as a cameraman, I am observing and interested, but I don’t yet have a goal of making a directorial film debut

— Would you like to make this project in Ukrainian or English?

— Perhaps the first film would have been in Ukrainian, because the language in the film should be organic. The most important thing is the story. Maybe something from another universe — science fiction, for example. I like it when there is visual and technical material. It would probably be a drama whose events take place in space 100 years from now. Maybe with a Ukrainian context. It would be interesting if an American, a Frenchman, and a Ukrainian met each other. And it’s cool when the nature of the states is shown, not just when it’s dudes without context.